Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg:

Building an Art Collection, a Study in Passion, Purpose, and Preservation

- Winifred Smith

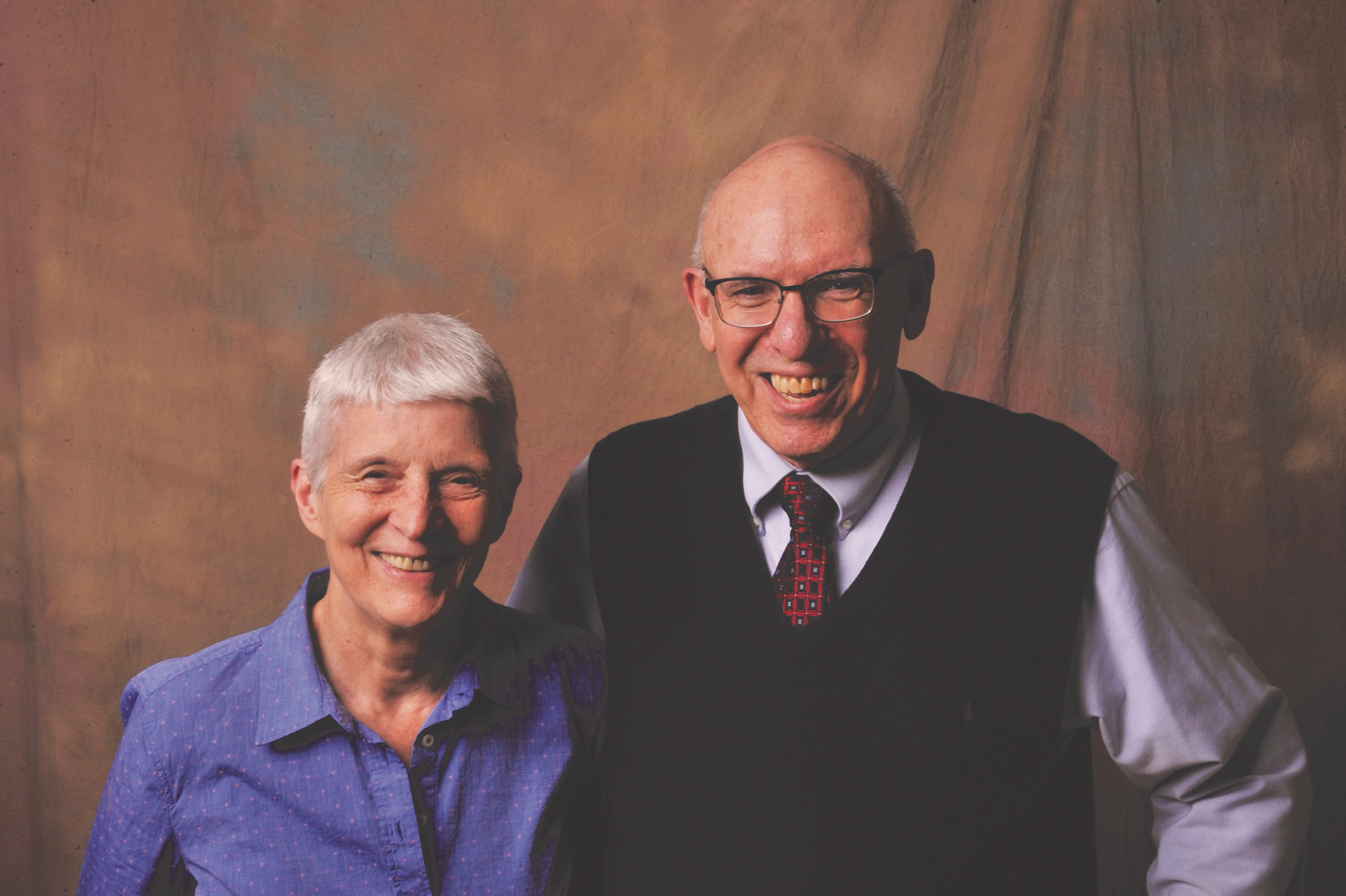

While it is possible to separate the Weisberg Collection from Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg, it is nearly impossible to separate Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg from the artworks they collect. That’s because, with their first purchase fifty years ago, the couple has been intent on finding neglected or little-known European realists, artists whose subject matter was the life around them, particularly the quiet dignity of common people. Without the Weisbergs sniffing out this art across Europe—in attics, dealers’ back rooms, and flea markets—many of the more than 200 drawings, paintings, and prints in this collection would have been lost to the ages, along with the names of the artists who made them. Due to the Weisbergs’ scholarship and persistence, art historians and casual viewers alike now have many more portraits, landscapes, and small narratives of daily life to help round out their understanding of Realism and Naturalism in nineteenth-century France and Belgium. As Taylor Acosta, a former doctoral student of Dr. Weisberg’s, puts it, together the pair exemplify, par excellence, “scholar, teacher, curator, collector.”1

Almost from the moment Gabe Weisberg spotted the Swiss-born Yvonne Herzog on the deck of an ocean liner in 1966, the two have shared a passion for bringing forgotten artists to light, educating people about them and promoting their reevaluation within the academic discourse. They bought their first realist drawing in 1970, early in Gabe’s career as a university professor and curator. The subject, a ragpicker, set the tone for much of the art they would later collect—the work of realists who devoted themselves to capturing true-to-life images of people who often were invisible in society. For years, the couple spent summers driving through small French villages, visiting collectors, toiling in the archives of regional museums, and knocking on the doors of artists’ descendants. “They did the hard work of finding these works, including a lot of sleuthing,” says art historian Laurinda Dixon, another of Gabe’s former students. “They are the Holmes and Watson of art history, and I can’t imagine one without the other.”2

The Formative Years

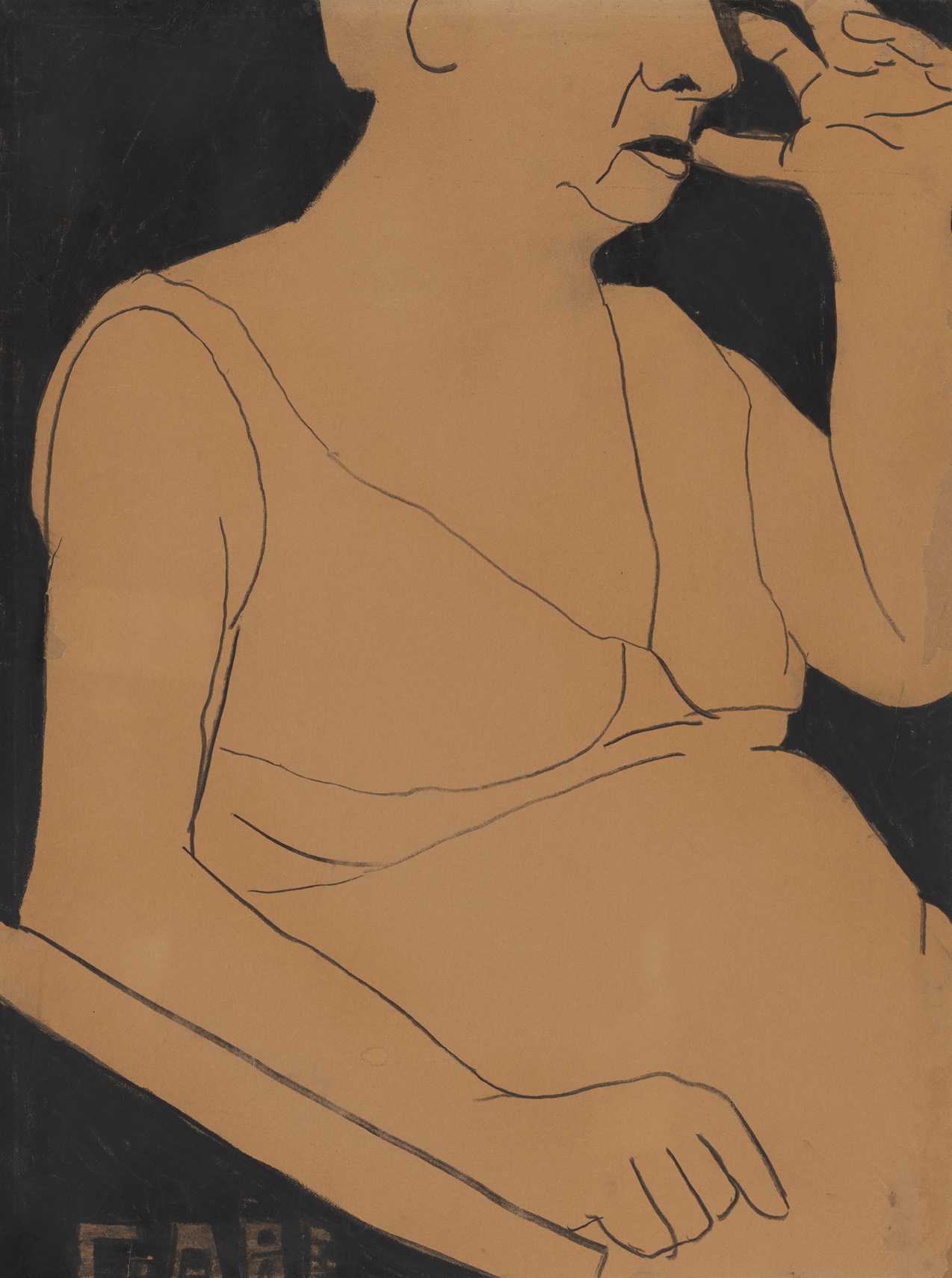

Despite a rather inauspicious first visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with his mother as a young boy, where he is reported to have said, “I’m never going to another museum,” Gabriel Paul Weisberg has dedicated his life to studying art and curating museum experiences designed to engage, inform, and enlighten. Born in New York on May 4, 1942, to Sarah Stollak, a high school English teacher, and Harry Weisberg, a CPA who was first a revenue agent for the government, Gabe attended P.S. 187, in Queens. A teacher recognized his artistic leanings and suggested that he enroll in classes at the Art Students League. While working from live models on Saturday mornings, he met the artist Alice Harold Murphy (1896–1966), who helped him build a portfolio and encouraged him to apply to the High School of Music and Art in Harlem (now Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts). There, Gabe received his first exposure to art history as a discipline. A drawing he made of his mother (fig. 2) demonstrates an early preference for the intimacy of a sketch. It also marks the beginning of his lifelong fascination with the creative impulse and the artistic skill that can be revealed through drawing.

After one semester at Ohio Wesleyan University, Gabe transferred to New York University. He majored in art history, focusing on nineteenth-century European art and the Northern Renaissance. After graduating in 1963, he pursued a master’s degree and doctorate at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, finishing both in four years. The financial aid was a draw, as was the possibility of being mentored by the school’s renowned art historian Adolf Katzenellenbogen, a medievalist and Holocaust survivor. Sadly, he died during Gabe’s second year.

Gabe then worked with Christopher Gray (1915–1970), an expert in nineteenth-century art history with an emphasis on the decorative arts. Gray spurred Gabe’s interest in the decorative arts (fig. 3) and inspired his doctoral thesis and subsequent book, The Independent Critic: Philippe Burty and the Visual Arts of Mid-Nineteenth Century France (1993). The choice of a French art critic whose name was then familiar only to specialists and whose influence extended across the broad sweep of nineteenth-century visual arts set the stage for Gabe’s own scholarship and collecting: uncovering deserving figures and broadcasting their accomplishments. Gabe stated in his preface: “Perhaps Philippe Burty will now have regained his voice and later scholars and writers on nineteenth-century art will never again be tempted to dismiss his contribution.”3 So, too, might this be said of almost every artist in the Weisberg Collection.

Yvonne Herzog Weisberg was born near Geneva, Switzerland, on May 14, 1942. Like Gabe, she was an only child. She had an adventuresome spirit and, at age sixteen, traveled with her cousin Nelly and their grandparents to Italy, where Yvonne shepherded her cousin to museums in Sienna, Florence, Pisa, Ravenna, and Venice. Despite no formal academic training, Yvonne benefited from these early experiences, which offered their own rich education in art history. She attended a college for social work in Lausanne and focused on working with children. She then moved to the town of Solihull, near Birmingham, England, to learn English—she liked American music, she says, and wanted to know what the songs were saying. She supported herself as an au pair for a young English family with four little girls.

In 1966, after a stay with a great-aunt in Victoria, British Columbia, the twenty-four-year-old Yvonne decided to return home to Geneva by way of New York. She was originally scheduled to depart on the Cunard line, but, as fate would have it, Cunard was on strike. Her ticket was changed to a Holland America passenger ship bound for Le Havre, France. She was standing on the deck when a young American approached, asking, “Do you play Ping-Pong?”4 He needed a fourth for a game of doubles. Averse to air travel, Gabe was heading to France by boat to research his doctoral thesis; his father, who planned to help with the legwork in Paris, chose to fly.

It took just six days on the boat (fig. 4) for Gabe to decide that Yvonne was the one for him. Yvonne, similarly inclined, needed a few more days together in Paris. In addition to introducing her to his (very surprised) father, Gabe introduced Yvonne to the Musée du Louvre, Musée Gustave Moreau, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and Jeu de Paume. The pair decided that they each had found their life’s partner. And in one of the world’s most romantic settings, Gabe proposed on a bench in the Tuileries gardens. Yvonne proceeded to Geneva, and Gabe—now highly motivated—returned to Johns Hopkins and completed his degrees. After a year of letter writing, they were once again brought together by a steamship when Yvonne docked in New York harbor and they were reunited. They married in New York on July 23, 1967, and since then have hardly spent a day apart.

“Galvanized by His Example”

Any discussion of the Weisbergs as collectors must begin with an understanding of Gabe Weisberg as a teacher. He began his career as an assistant professor of art history at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. After two years (1967–69), the couple decided that they needed to be closer to New York and major collections of nineteenth-century art.

From 1969 to 1973, Gabe taught at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, where he helped start the graduate program in art history. The Weisbergs developed lifelong connections there with a talented group of students, a number of whom went on to have successful careers as university art historians, museum curators, and government officials. Laurinda Dixon, professor emerita of art history at Syracuse University, in New York, is a celebrated author, lecturer, and academician. She was an eighteen-year-old music major when she took her first Weisberg class. She remembers Gabe as a wunderkind who sparked her love of art history. “He had tremendous personal responsibility about getting the information to his students; everyone was galvanized by his example,” she says.5 Another former student, Roger S. Wieck, is a world authority on medieval books of hours and heads the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. Former student Peggy A. Loar spent nine years as director of the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES), then headed several museums, including the Wolfsonian in Miami and Genoa, Italy, and the National Museum of Qatar.

Gabe’s first opportunity to organize an exhibition came in the 1970s. His collaborator was Frank Sanguinetti, the energetic new director of the fledgling Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) in Salt Lake City, who was looking for ways to raise the museum’s profile. Together they mounted three exhibitions at UMFA: “The Etching Renaissance in France: 1850–1880”; “Social Concern and the Worker: French Prints 1830–1910,” which also traveled to the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Indianapolis Museum of Art; and “Images of Women: Printmakers in France from 1830 to 1930.” These experiences reinforced Gabe’s belief in the role that art plays in history, helped establish his reputation as a print curator, and fueled his and Yvonne’s nascent interest in collecting.

A Milestone in Cleveland

Curating learning opportunities for museum visitors returned Gabe to his great love: research. This led him to leave academia for a time to become curator of art history and education at the Cleveland Museum of Art (1973–81). The importance of the Weisbergs’ time in Cleveland cannot be overstated. It solidified the partnership between Gabe and Yvonne as a research team and strengthened Gabe’s bona fides as a scholar. This is also when the couple fully realized that the nineteenth-century realists were gifted artists with particularly astute social and political insights, and devoted themselves to exploring this untapped area of scholarship.

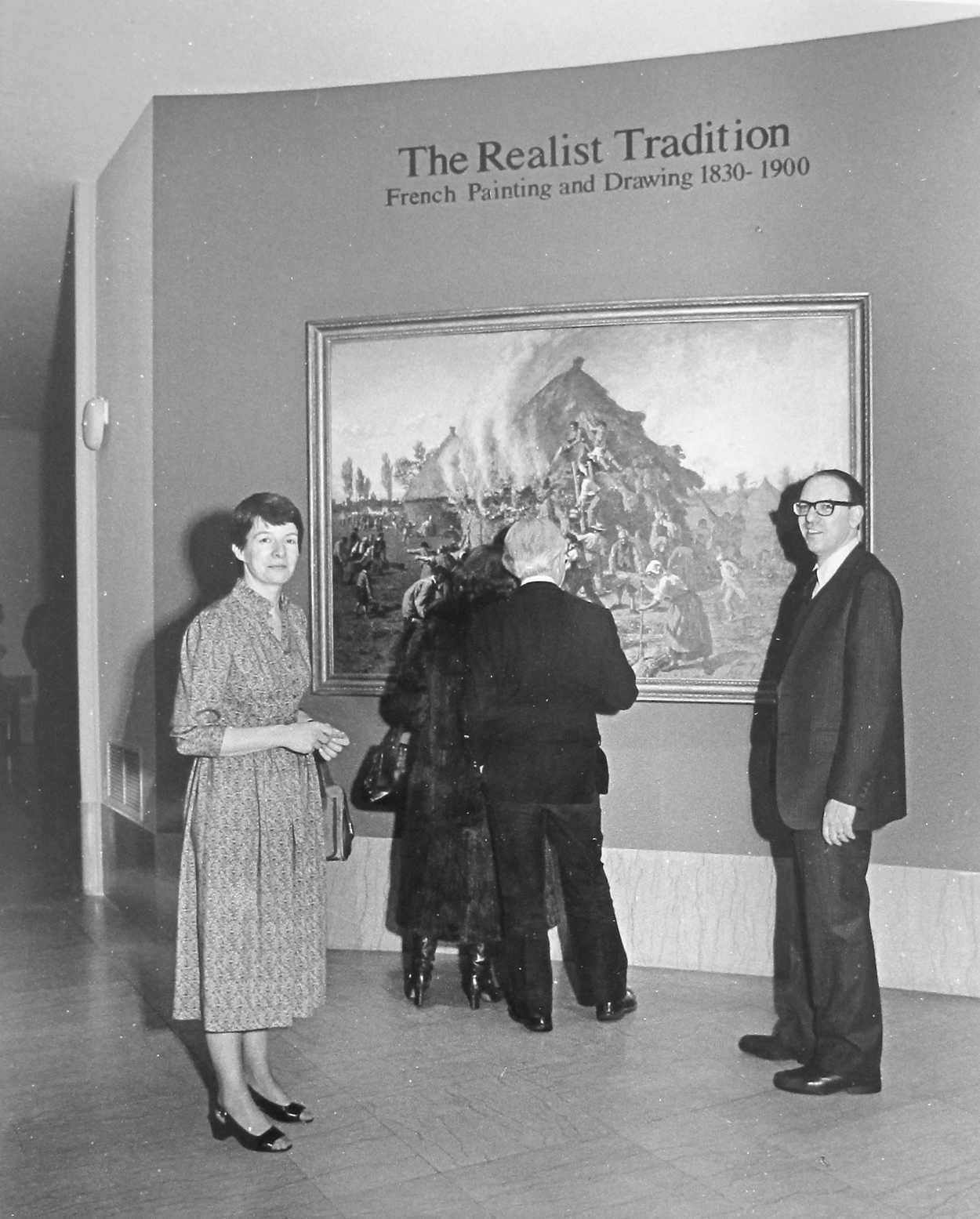

At Cleveland, Gabe organized groundbreaking exhibitions that revealed new insights into how nineteenth-century life and art influenced each other. In his review of Gabe’s first effort in Cleveland, “Japonisme: Japanese Influence on French Art 1854–1910,” New York Times art critic John Russell described the show as “a full-scale attack, in which paintings, prints, theater programs, bookbindings, wallpaper, furniture and the decorative arts all play a part” and reported that it drew “large and conspicuously attentive crowds.”6 Gabe’s pièce de résistance, however, was “The Realist Tradition: French Painting and Drawing 1830–1900,” a landmark exhibition that opened in Cleveland in 1980 (fig. 5) and traveled to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; St. Louis Museum of Art; and Glasgow (now Kelvingrove) Art Gallery and Museum, Scotland. It included some 240 works on loan from museums worldwide; the accompanying catalogue is considered the seminal text on the decades-long realist movement in France.

This highly acclaimed show helped establish what we understand today to be French Realism, examining the artists’ relationships with one another, their influences, and their roles as faithful chroniclers of everyday life in France. To gather information, Gabe and Yvonne traveled throughout the provincial areas of France, going through museum storage areas, charming their way into the homes of private collectors, and visiting dealers with knowledge of regional art. These conversations introduced the couple to artists whose names they didn’t know, such as Philippe Auguste Jeanron and Claude Joseph Bail. “They are incredibly good at archival research. They will do the family background, find the descendants of artists, and visit descendants,” says Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, an expert on nineteenth-century European art, commenting on the disciplined approach of the Weisbergs’ research.7

While preparing “The Realist Tradition,” Gabe spent nearly a year (1979–80) at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where scholars can concentrate on research projects in an idyllic setting. In 1982, shortly after leaving Cleveland, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship, which supported him and Yvonne while they conducted research on the influential Paris gallerist Siegfried Bing. Gabe subsequently became a senior fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. These opportunities, though they offered time to investigate, access to extensive libraries, and the company of fellow scholars, were temporary. After two years as assistant director of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Gabe was ready to interact with students again.

The second half of his career was launched in 1985, when he joined the faculty at the University of Minnesota, encouraged by Marion Nelson, who taught art history there, and Lyndel King, director of the Weisman Art Museum on campus. Within a year, Gabe was a full professor. Nearly every semester, he took students to the Herschel V. Jones Print Study Room at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) to experience prints firsthand. He became a mentor to students who built successful careers in art history, notably the curators Lisa Dickinson Michaux (Minneapolis Institute of Art), Nikki Otten (Milwaukee Art Museum), and Taylor Acosta (Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska). In 2012 Gabe’s excellence in illuminating the field won him that year’s prestigious art-history teaching award from the College Art Association (fig. 6). And, in gratitude for Gabe’s own opportunities for research, the Weisbergs endowed a fellowship through the University of Minnesota Foundation and the Department of Art History. Established in 2015, the Gabriel P. Weisberg Curatorial Award supports undergraduate and graduate students working on projects with Twin Cities museums.

Bonvin Sets the Tone

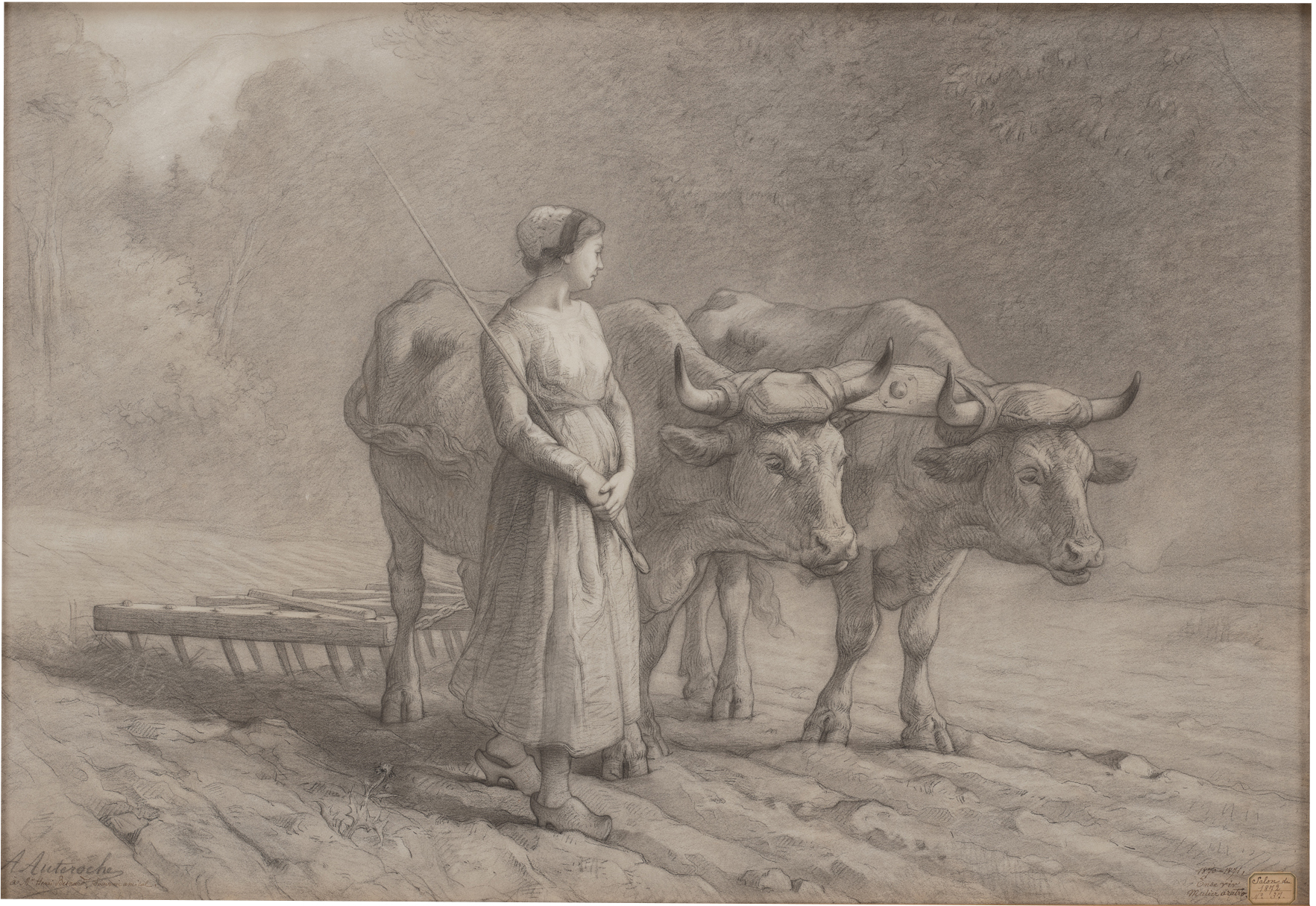

Gabe was still teaching in Cincinnati in 1970 when he and Yvonne bought their first realist work, The Old Beggar (fig. 7), a chalk drawing by François Bonvin (1817–1887). They acquired it while in Europe researching Realism and preparing a book on Bonvin. Word of the drawing had come from Gabe’s mother, who saw it in a catalogue from the Hazlitt Gallery in London; she reached the couple in Switzerland and encouraged them to see it. Eventually, the Weisbergs would own seven works by Bonvin, but this drawing is one of their most treasured—both for its quality and for what it meant: though still in their twenties and with limited resources, it was their first step toward owning the kind of art they researched. Bonvin likely found the figure on the street and invited him to his studio to model. This connection between life and art, which the Weisbergs believe can be made only upon close examination and contemplation, became a thread for nearly everything in the Weisberg Collection that followed. Certain qualities of the drawing became collection hallmarks: an underappreciated artist who, through exceptional craftsmanship, had the ability to tell a story about the sitter, usually someone of humble origins. As observed by Michaux, a former curator of prints and drawings at Mia, “With drawings, you really get to see the hand of the artist—they are so much more precious and are used by scholars to tell the story of the artist.”8 Above all, The Old Beggar confirms that a drawing should be seen as a complete and finished work of art.

In the years after Bonvin died, his work was overshadowed by large-scale realist paintings, especially those by his one-time friend Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), the self-described father of the realist movement. The Weisbergs’ research revealed that Bonvin was a largely self-taught artist with a well-developed eye for detail and a sensitivity for his subjects. In 1971 one of Gabe’s former students at the University of Cincinnati, the scholar Richard S. Schneiderman, alerted the couple to a Bonvin painting in the possession of an East Coast dealer. This was Up from the Cellar (fig. 8), one of several small oil paintings in the Weisberg Collection. The artist portrayed a young woman and her surroundings with characteristic attention to detail—her clean white apron and bonnet suggest that she may be a household servant. Despite the hard work, her countenance conveys honor and dignity. The hexagonal floor pattern and treatment of light and contour demonstrate Bonvin’s affinity for seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French and Dutch masters. Ultimately, Gabe’s research into the artist resulted in the book Bonvin, published in 1979.9 Museums and private collectors eventually caught on to this neglected talent, and the Weisbergs have since faced stiffer competition for his drawings.

The Hunt for Milcendeau

Beginning with François Bonvin, the Weisbergs resurrected a succession of accomplished artists who together have helped define nineteenth-century Realism more fully. Although they acquired realist examples by Belgian, German, and Swiss artists, the vast majority of artists in the collection were born in France. Perhaps no artist represents the couple’s decades-long curiosity, tireless work ethic, and dedication to the slow, methodical research process than Charles Milcendeau (1872–1919),10 one of the couple’s most significant discoveries and an artist left out of the pioneering “Realist Tradition” exhibition simply because none of the contributors was aware of him. To date, the Weisberg Collection includes fourteen Milcendeau drawings, believed to be the largest compilation of his work outside of the Charles Milcendeau Museum (fig. 9), in the artist’s hometown of Soullans, in France’s Vendée region.

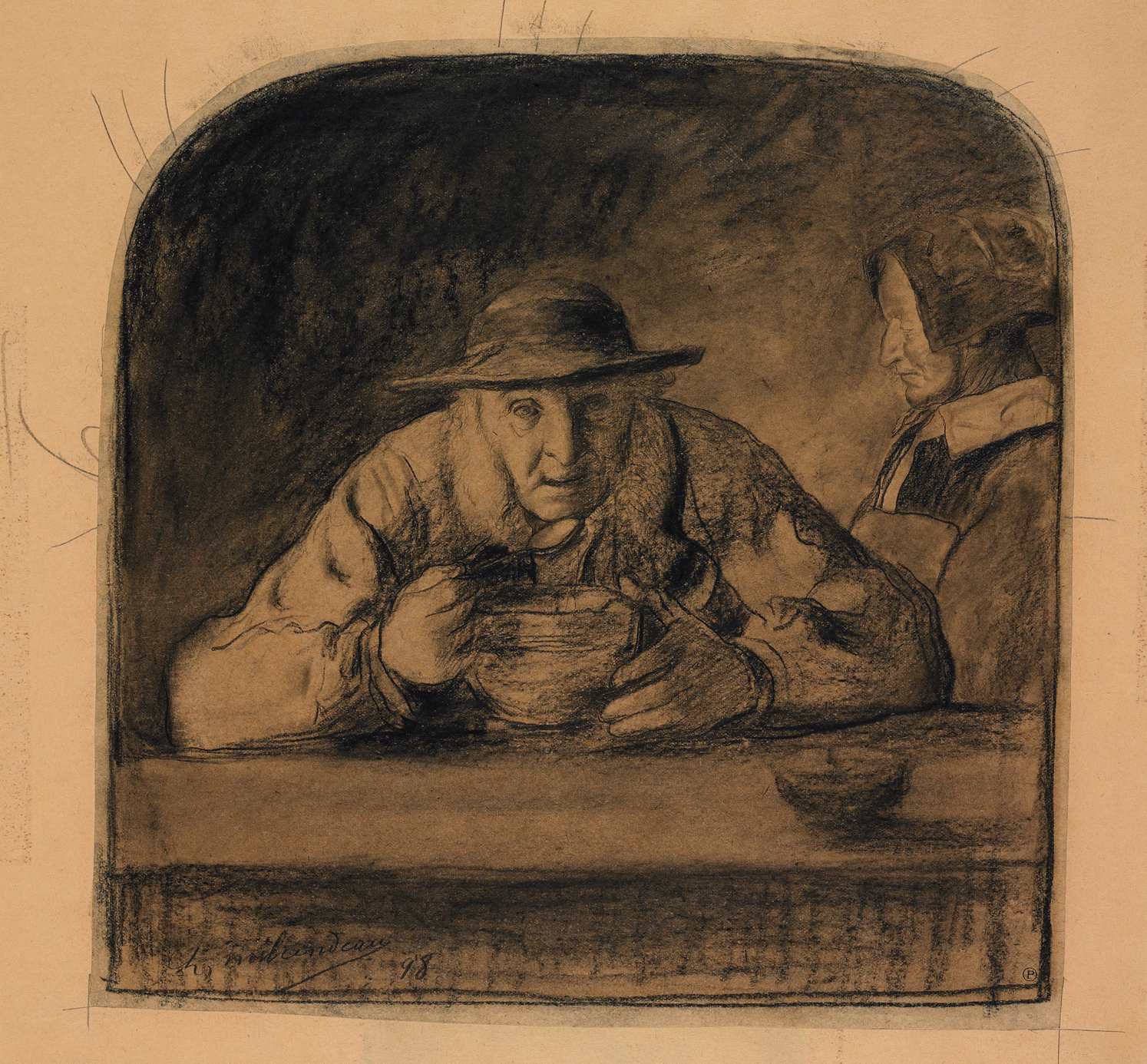

Yvonne and Gabe’s revival of Milcendeau can be traced to a visit to Paris in 1993, when the Weisbergs wandered into Galerie Fischer-Kiener, a frequent stop for them, after an afternoon at the Musée d’Orsay.11 Leaning against a piece of furniture was a 1915 drawing of Milcendeau’s house on Chemin du Bois Durand (cat. no. 139). Gabe wanted to know more. Within days, he and Yvonne were driving—with Yvonne behind the wheel as always (Gabe never learned to drive)—to the Milcendeau Museum, four and a half hours away. Thus began the long journey to give Milcendeau his due. Every new drawing deepened the couple’s appreciation of the skill and honesty with which he set his subjects to paper. “We fell in love with the artist and saw that he was able to give compelling expression to the challenges in the lives of everyday people,” Yvonne says.12 Before leaving Paris, the couple had already acquired a second Milcendeau drawing (fig. 10).

Born in 1872, Milcendeau studied with Gustave Moreau, a leading figure at the École des Beaux-Arts. Two of Moreau’s other students were Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, who became Milcendeau’s friends. Milcendeau had a significant following in France during his lifetime. He was respected among his contemporaries and exhibited at notable venues, such as Galerie Georges Petit. He excelled in drawing, pastel, and gouache, and was known for his insightful portrayals of those at the lowest levels of society. In 1901 the French government acquired his pastel Mother and Two Children, which Gabe called “majestic.”13 Through years of research, the Weisbergs also discovered that in 1904 Milcendeau had exhibited in the Carnegie International exhibition in Pittsburgh and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Why, then, did he all but disappear from view? The Weisbergs cite the artist’s unwillingness to adjust his subject matter to changing tastes. As Gabe wrote in a catalogue essay for the 2012 exhibition “Milcendeau, le maître des regards” in Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne, France, “Milcendeau is a follower of realism, I would say even social realism. His work is that of an activist.” His integrity demanded that he stay true to his artistic vision. “To appreciate Milcendeau one must become interested in scenes linked to the life of the peasant and recognize an artist of infinite power and insight whose best works were often done as charcoal drawings, pastels, or gouaches on a very limited scale. Only then will the visitor be able to grasp the artist’s range.”14

The Path of Committed Collectors

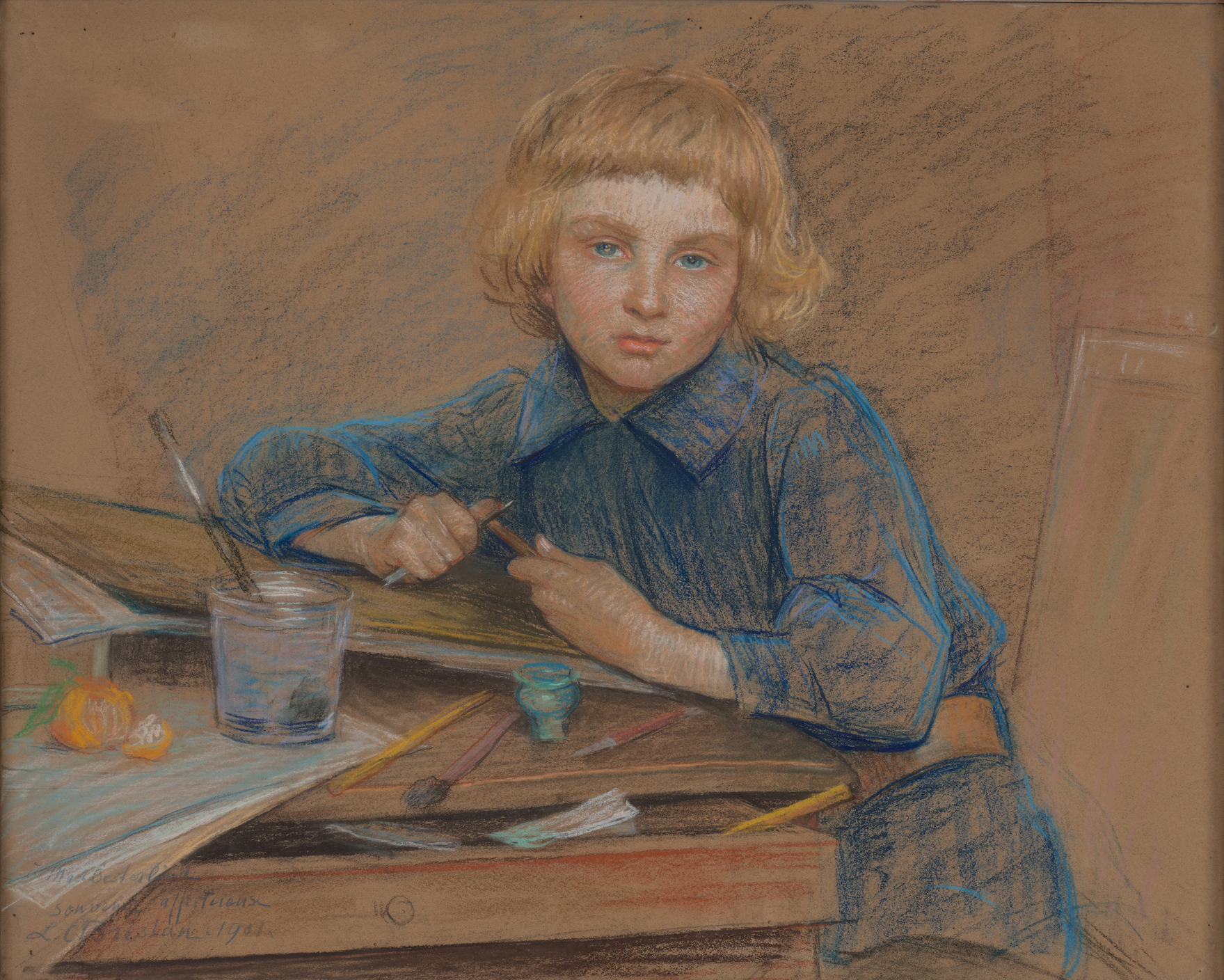

Among the Weisbergs’ favorite sources for finding unsung nineteenth-century artists were Paris flea markets, especially the one at Porte de Clignancourt. There, they largely had to rely on instinct. An early discovery was an 1865 drawing by Alexandre Abel de Pujol, a chalk sketch in pristine condition (cat. no. 159). Another time, they picked up the watercolor Reverie (c. 1884) by Louis Welden Hawkins (cat. no. 84). This was in 1995, and, incredibly, a dealer had it lying on the floor. The Weisbergs’ practiced eye also brought Henri Vever into their collection with a pencil drawing of his four-day-old daughter, Marguerite (cat. no. 183). A collector and a goldsmith, Vever headed the venerable Paris jewelry firm Maison Vever.15 The Paris flea market also yielded an important 1901 pastel by Louise Catherine Breslau, The Study of Drawing: Portrait of Yves Österlind, Age Nine (fig. 11). Born in Switzerland, Breslau had moved to Paris at age nineteen to study at the Académie Julian, one of the few places that admitted female students. Among her many accolades was a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in 1889. In 1901 she became the first foreign female artist to be awarded the Legion of Honor. As this pastel illustrates, Breslau was especially gifted at portraits of children.

Art dealers have also been indispensable to the Weisbergs’ quest, particularly Shepherd Gallery in New York, and the Parisian dealers Jane Roberts, André Watteau, Jacques Fischer, and Chantal Kiener. The couple met Fischer and Kiener through Noah L. and Muriel Butkin, Cleveland Museum of Art benefactors who became close friends during the Weisbergs’ Cleveland years. Gabe counseled the Butkins about artworks they contemplated buying, and they in turn helped the Weisbergs understand the international art market and the insights that art dealers could provide. While still novices, the Weisbergs bought a handful of drawings from Shepherd, including their first work by Théodule Ribot. The couple learned that Ribot was a good friend of François Bonvin—one of many connections that would help their collection cohere. In 1980, upon the death of Noah Butkin, Muriel gave the couple Bonvin’s 1856 drawing Seated Old Woman Holding a Cane (cat. no. 30), and it holds a special place in the collection.

Fischer and Kiener shared the Weisbergs’ love of nineteenth-century French draftsmanship. Their former gallery, at 46 rue de Verneuil, was a perennial stop on the Weisbergs’ yearly trips to Paris. In time, the two dealers came to know their clients’ tastes: no fewer than forty-two works in the Weisberg Collection came from Galerie Fischer-Kiener, or from Jacques Fischer and Chantal Kiener working separately. In fact, it was Fischer-Kiener employee Christine Bethenod who told the Weisbergs about the Milcendeau Museum. After Bethenod became a dealer, the Weisbergs began buying from her as well.

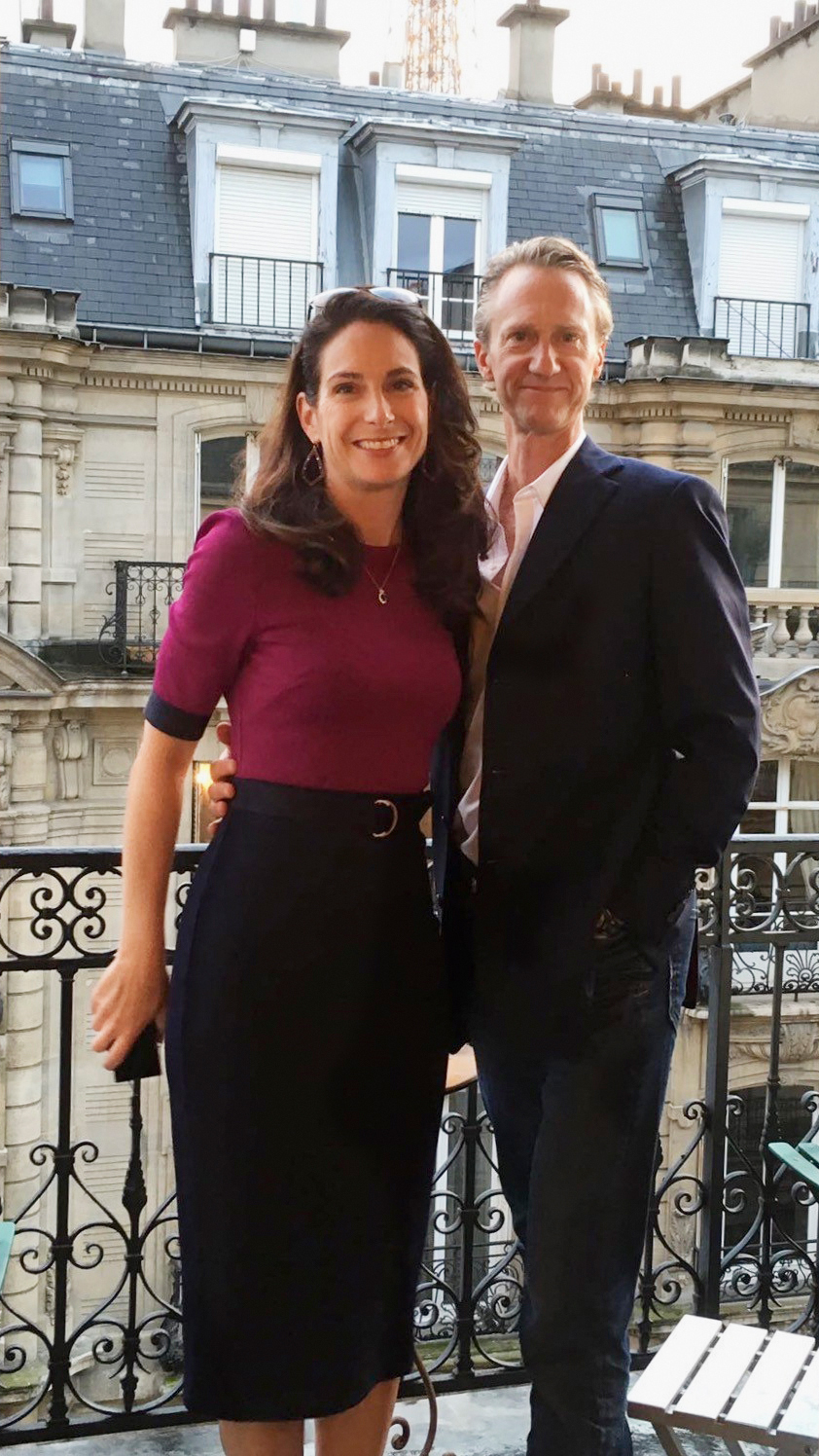

They also developed an important relationship with Paris dealer Jane Roberts, both as an arts professional and—as is the couple’s wont—a close personal friend (fig. 12). She eventually took on a more strategic role, suggesting acquisitions to fill in holes or enhance the collection. Examples are Milcendeau’s highly finished 1898 charcoal Making Butter, Brittany Interior (cat. no. 132) and Lucien Ott’s A Tanner Smoking His Pipe from 1918 (cat. no. 152).

The Weisbergs never bought anything from André Watteau; his prices were simply out of their reach. Yet Gabe credits the late gallery owner with deepening his engagement with Bonvin and Ribot. The couple spent a great deal of time at Galerie André Watteau on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, looking at art and becoming educated about these artists. Watteau encouraged Gabe to write Bonvin in 1979, when the artist was barely known to the general public. Watteau translated the text into French. To commemorate their mutual respect and affection, Watteau presented his friends with two Ribot drawings, Interior of a Kitchen (cat. no. 161) and Studies of Hands (cat. no. 164).

Partners in Research

In a now-familiar pattern, Minnesota entrepreneur Brad Radichel also gave the couple a drawing in the name of friendship—the 1896 Milcendeau charcoal Beggar with a Bottle (cat. no. 129). Radichel is one of the many collectors whom the Weisbergs have taken under their wing, sharing their knowledge as generously as others had with them. When they first met, Radichel wanted to collect art but was unsure how to narrow his focus. He remembers the Weisbergs’ early guidance as an “intensified exploration of the world of art and my ‘schooling’ in important concepts such as the chain of provenance, the condition of a work, the nature of its imperfections, the quality of restoration, and so on,” he says. “I learned that there is no substitute for scholarly due diligence and the confirmation of claims.” Twenty years later, Radichel has amassed a remarkably cohesive collection of paintings by nineteenth-century French and Belgian artists, among them Alphonse Legros, Jules Bastien Lepage (fig. 13), and Léon Frédéric. When Radichel decided to publish a catalogue of his paintings, he asked Gabe and Yvonne to help write it.16 “There is rarely a paragraph spoken by Gabe which is not emphatically confirmed or corrected by Yvonne,” he says of their partnership. “The combination of input from the two ensures an accurate and insightful conclusion.”17

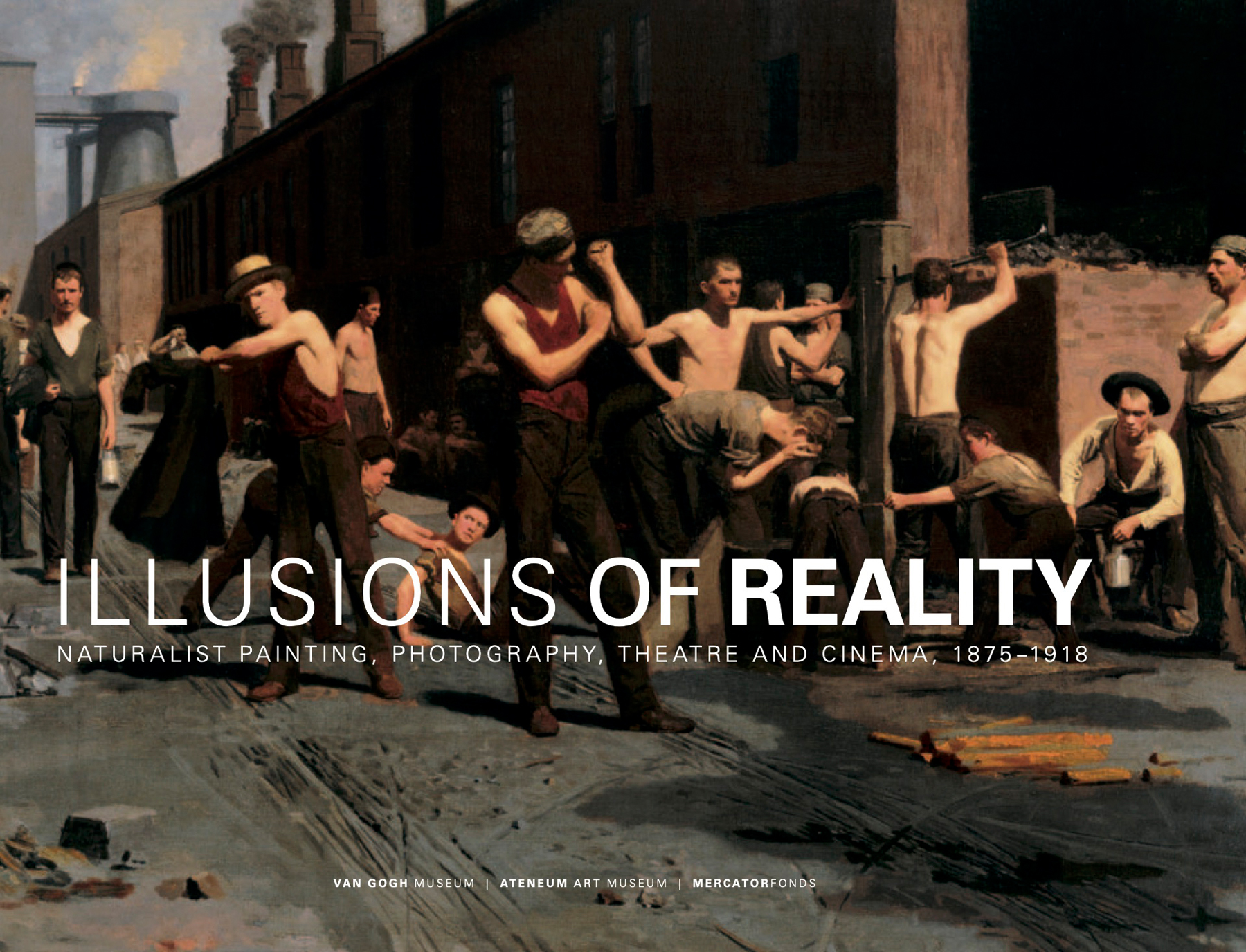

Indeed, Gabe has published widely over his career, with Yvonne his ever-present research partner. This writing and editing have centered around French artists and their involvement not just in Realism but also in Japonisme, Art Nouveau, Naturalism, and academic painting. Often Gabe’s writings relate to his exhibition topics. Shortly after arriving in Minnesota, for example, the couple’s years-long labors on Siegfried Bing resulted in “Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900,” presented at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in Richmond, in 1986, under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution. Then followed a 1991–92 Regents’ Fellowship residency for Gabe at the National (now Smithsonian) Museum of American Art, in Washington, D.C.18 In 1999 he co-curated “Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian,” which originated with the Dahesh Museum of Art, in New York. Gabe and Yvonne revisited Bing in a 2004 exhibition he also co-curated, “L’Art Nouveau: The Bing Empire,” at the Van Gogh Museum, in Amsterdam. For this same museum, Gabe curated a show in 2010 examining Naturalism, titled “Illusions of Reality: Naturalist Painting, Photography, Theatre and Cinema, 1875–1918” (fig. 14).

The next year, he again brought his pioneering investigations into Japonisme to bear by organizing “The Orient Expressed: Japan’s Influence on Western Art, 1854–1918,” which traveled to Jackson, Mississippi, and San Antonio, Texas. In 2012 he paid tribute to the Butkins by mounting an exhibition at the University of Notre Dame’s Snite Museum of Art that included the Snite’s many Butkin-donated works of nineteenth-century French art. Gabe also led the curatorial team—and edited the catalogue—for “Japanomania in the Nordic Countries 1875–1918,” which traveled to Helsinki, Oslo, and Copenhagen starting in 2016 (fig. 15).

In 2018 Gabe became professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota. Not one to let retirement slow him down, he lent his expertise to the exhibition “Théodule Ribot: Une délicieuse obscurité,” which traveled to the French cities of Toulouse, Marseille, and Caen during 2021–22. He also curated “B.J.O. Nordfeldt: American Internationalist,” which stopped at the Wichita Art Museum, in Kansas, before opening at the Weisman Art Museum in 2022. Meanwhile, he completed a major catalogue essay about Léon Bonvin, François’s lesser-known yet talented half-brother, for an exhibition that opened at Paris’s Fondation Custodia in October 2022 (fig. 19).

A Permanent, Public Home

For years, the Weisbergs (fig. 16) have steadily donated works to Mia, such as the Breslau pastel (fig. 11), given in 2019 in memory of Michael D. Michaux. His wife, Lisa Dickinson Michaux (fig. 17), rose to become associate curator in Mia’s former Department of Prints and Drawings, and the two couples remained very close. The Weisbergs credit their bond with Lisa Michaux to their decision, announced in 2008, to bequeath their entire collection to Mia. Evan Maurer headed the museum when the couple first discussed making Mia the permanent home for their collection. “Gabe and Yvonne are the epitome of passionate collectors devoted to the museum as a place for continued learning,” he says. “The Weisbergs will always be noted as among our greatest collectors and donors in this area, not just in our community, but as a resource for the world.”19 And in trusting their collection to Mia, he adds, they will have realized their goal of making sure that their artworks are “preserved for posterity.” To recognize the Weisbergs’ generosity, Michaux organized “Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection.”

The 2008 exhibition and accompanying catalogue20 (fig. 18) included forty-eight drawings. Back then, the collection comprised about 125 works of art. It now tops 200 works and continues to grow, making it one of the most comprehensive collections of nineteenth-century drawings in the country.

In May 2022, just after the opening of Mia’s more in-depth exhibition “Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection,” Mia Director and President Katie Luber celebrated the couple at a gathering of their friends and colleagues. “The Weisbergs’ contributions to art history, to their students and protégées, and to their community have touched countless lives,” she said. “They have challenged conventions and dug deep to bring to light the careers of artists and other cultural figures whose work continued to reverberate even as it was forgotten.”21 And in the process, the couple has built a fascinating collection that they are giving to the public for everyone to study, interpret, and enjoy. Mia is honored that the Weisbergs have trusted it with their collection, Luber added, and will ensure that it is well cared for.

Notes

Taylor Acosta telephone conversation with the author, June 16, 2020. ↩︎

Laurinda Dixon telephone conversation with the author, June 11, 2020. ↩︎

Gabriel P. Weisberg, The Independent Critic: Philippe Burty and the Visual Arts of Mid-Nineteenth Century France (New York: P. Lang, 1993), preface, p. xv. ↩︎

Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg interviews with the author conducted on February 5, 25, and March 12, 16, 2020. ↩︎

Laurinda Dixon telephone conversation with the author, June 11, 2020. ↩︎

John Russell, “On Art: ‘Japonisme’ Stirring Cleveland,” New York Times, August 23, 1975, p. 19. ↩︎

Petra Chu telephone conversation with the author, June 10, 2020. ↩︎

Lisa Michaux conversation with the author, June 8, 2020. ↩︎

Gabriel P. Weisberg, Bonvin, trans. André Watteau (Paris: Éditions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1979). ↩︎

For more on Milcendeau, see Alain Jammes d’Ayzac, Charles Milcendeau: Le maraîchin (Paris: Éditions de Flore, 1946). This was reprinted with a preface by Christophe Vital for the 2012 exhibition Milcendeau, le maître des regards, at Historial de la Vendée, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne. The Weisbergs loaned several works to this show. Gabriel Weisberg wrote about the show in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012). ↩︎

Gabriel and Yvonne Weisberg conversation with the author, September 16, 2020. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Weisberg, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, p. 4. ↩︎

Weisberg, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, p. 1. ↩︎

For more on Vever, see Willa Z. Silverman, ed., Henri Vever: Champion de l’Art Nouveau (Malakoff, France: Armand Colin, 2018). ↩︎

Gabriel P. Weisberg, Janet L. Whitmore, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, and Yvonne M. L. Weisberg, Toward a New 19th-Century Art: Selections from the Radichel Collection (Minnetonka, Minn.: Books & Projects, 2017). ↩︎

Brad Radichel email exchange with the author, November 17, 2020. ↩︎

https://americanart.si.edu/research/fellowship/fellows/gabriel.p-weisberg, accessed on July 3, 2022. ↩︎

Evan Maurer telephone conversation with the author, May 27, 2020. ↩︎

Lisa Dickinson Michaux with Gabriel P. Weisberg, Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection (exh. cat.), Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis: 2008). ↩︎

Katie Luber at a reception honoring the Weisbergs, May 19, 2022. ↩︎