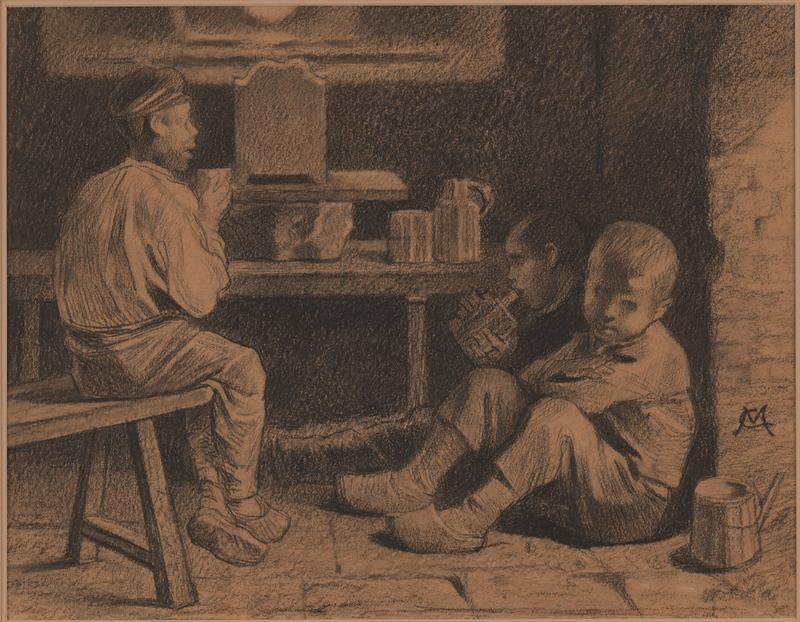

127. Constantin Meunier, Young Boys at Rest

| Artist | Constantin Meunier, Belgian, Etterbeek (Brussels) 1831–Ixelles (Brussels) 1905 |

| Title, Date | Young Boys at Rest, c. 1880 |

| Medium | Charcoal on beige paper |

| Dimensions | 15 9/16 × 19 7/8 in. (39.5 × 50.5 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Monogram, lower right: CM |

| Provenance | Collection Caroline and Maurice Verbaet, Antwerp; [Mathieu Néouze, Paris, until 2015; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Exhibition History | "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| Credit Line | Promised gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Minneapolis |

Constantin Meunier, already a well-established painter with eighteen years of Salon exhibitions under his belt, found his raison d’etre in 1878. During a visit to the Borinage, a major coal-mining region in southern Belgium, he was deeply moved by his encounter with workers. From the 1880s on, he devoted his art to them, showing them as heroic and stoic and their working conditions as severe. His paintings, illustrations, and increasingly his sculptures brought him success and fame as an advocate for workers. In 1890 the French government bought a small version of his Blacksmith for the Musée du Luxembourg, a first for a foreign sculptor. Meunier was seen by many as the Belgian counterpart to French sculptor Auguste Rodin.

After Meunier died, a monographic exhibition of his labor imagery toured six American industrial cities, in 1913–14.1 The show drew large crowds. At the time, it was heralded as a tribute to labor, but some modern critics argue that the workers were portrayed as being too docile, accepting their fate rather than rebelling against it.2 Similar criticism is often leveled at realist art in general. A counter argument can be made that if socially conscious art had been considered too revolutionary in Meunier’s day, it would never have made it to the public stage.

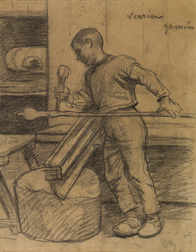

Meunier depicted workers of various ages and at various moments. The present sheet shows three young apprentices resting after their exertions. Another Meunier study exists of a young boy working in a glass workshop (fig. 1). This, combined with the similar direction of light (from the left) and the signs of thirst, suggests that these three boys may also be in such a workshop. (Meunier biographer André Fontaine noted that the artist studied the workers at the Belgian glassmaker Val Saint Lambert around 1878.3) In both drawings, Meunier confronted the viewer with the reality of child labor and industry’s effort to groom the next generation of workers.

The high finish of the present drawing tells us that this was not one of Meunier’s on-the-spot sketches like On the Way to the Mine (cat. no. 128). Instead, it appears to be preparatory to a painting or a book illustration.4

TER and GPW

Notes

Buffalo, Pittsburgh, New York, Detroit, Chicago, and St. Louis. See Melissa Dabakis, “Formulating the Ideal American Worker: Public Responses to Constantin Meunier’s 1913–14 Exhibition of Labor Imagery,” The Public Historian, vol. 11, no. 4 (Autumn 1989), pp. 113–32. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

André Fontaine, Constantin Meunier (Paris: Librarie Félix Alcan, 1923), p. 93, (hathitrust.org). Also see Armand Thiéry and Emile van Dievoet, Catalogue complet des oeuvres dessinées, peintes et sculptées de Constantin Meunier (Louvain, Belgium: Nova et Vetera, 1909). ↩︎

A small related oil on canvas (36 x 30 cm) was auctioned at Campo & Campo, Antwerp, March 10, 2009, no. 137. Entitled De twee kinderen, it showed the two boys at the right. Whether it is an unknown painting by Meunier or a copy of part of the present drawing by another artist is unknown. ↩︎