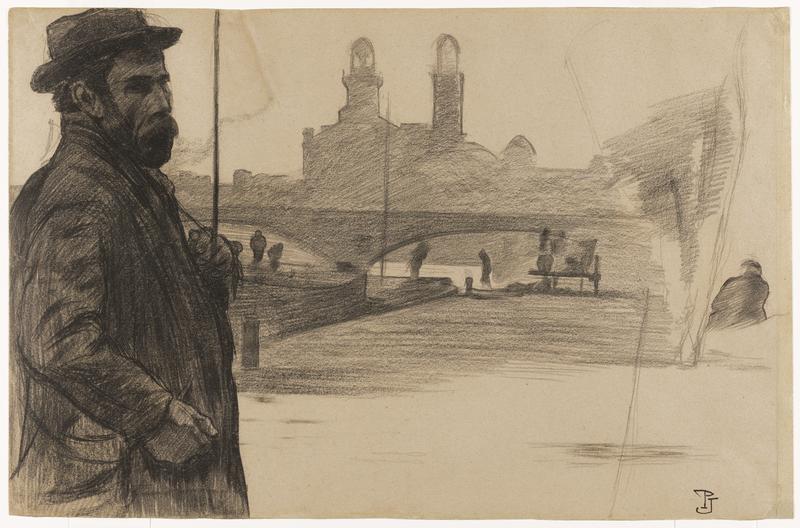

95. Pierre-Paul Jouve, Man along the Seine with a View of the Old Trocadéro

| Artist | Pierre-Paul Jouve, French, Bourron-Marlotte, Seine-et-Marne 1878/80–Paris 1973 |

| Title, Date | Man along the Seine with a View of the Old Trocadéro, c. 1903 |

| Medium | Charcoal on beige paper |

| Dimensions | 12 3/8 × 18 7/8 in. (31.4 × 47.9 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower right: PJ |

| Provenance | Probably sold Étude Couturier-Nicolay et Étude Daussy-Ricqlès, Drouot, Paris, 1991. [Galerie Jacques Fischer, Paris, until about 2005; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis (c. 2005–18; given to Mia) |

| Exhibition History | "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| References | Félix Marcilhac, "Paul Jouve: Peintre, sculpteur, animalier, 1878–1973" (Paris: Les Éditions de l’Amateur, 2005), p. 16, ill. |

| Credit Line | Gift of Dr. Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg 2018.117.14 |

Paul Jouve was one of the foremost Art Deco animaliers—that is, artists who specialize in depicting animals. Occasionally, however, he contributed illustrations to artistic and political journals. In 1903 he collaborated with critic Raymond Bouyer (1862–1935) on a two-part essay for Revue de l’Art Ancien et Moderne. Entitled “Les quais de Paris,” the piece spoke to the apprehensions his fellow artists might have had about portraying the great city.1 The author reasoned that the grand tradition of recording Paris by French artists (from Jacques Callot to Camille Corot) and international artists (from Reinier Nooms to Johan Jongkind) might intimidate contemporary artists, leaving them wondering what could be left to do. Bouyer wrote of Paris as a living, ever-changing place. Taking us on a tour along the banks of the Seine, he described the layers of architecture in the city—Gothic, Renaissance, classicized—and what he called the indecision of the nineteenth century with its historicized mishmash. He recalled monuments that had been destroyed, moats that had become gardens, trees that had grown, work lives that had changed. Through it all flows the Seine, always present but always different. The river becomes a metaphor not only for the life of the city but also for the imagination of successive generations of artists. Each artist can depict the Paris that he or she sees and imagines. Bouyer saw in Jouve a young artist ready to give Paris a new physiognomy in his luminous drawings.2

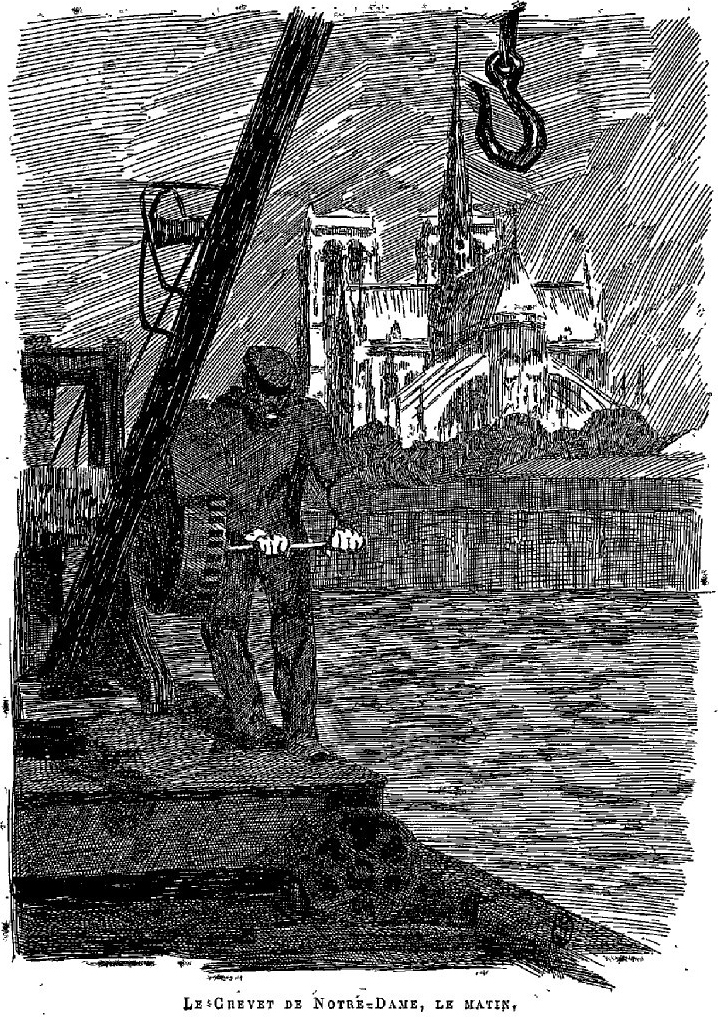

Ten of his drawings accompany Bouyer’s essay (fig. 1). Though Man along the Seine with a View of the Old Trocadéro is not a direct basis for any of these, its subject is closely connected to the project. It probably reflects the type of working study that would have preceded Jouve’s finished pen-and-ink illustrations. Such studies were likely made outdoors quickly, using a friable medium such as charcoal or conté crayon. Very responsive to pressure, the sticks of pigment would have enabled Jouve to make lines both faint and heavy, as he does here. With sketches in hand, he would likely have completed his final densely hatched scenes at home or in a studio.

Any Parisian would have recognized the foreground figure as a clochard, meaning a vagabond or tramp and more specifically a person without shelter who lived along the quays and slept under bridges. Such figures were often romanticized in French literature, but Jouve avoided idealization, seeking instead to capture in his subject’s hardened features and solemn expression the difficult existence of those down and out in the City of Lights.3 The figure’s possessions are in a bundle on his back, attached to the string he holds in his hand. An idle man sits nearby. Farther along the embankment, people have picked up some work transferring cargo between a wagon and a barge. By opening up the center foreground of his image, Jouve suggested the loneliness and desolation such people may experience.

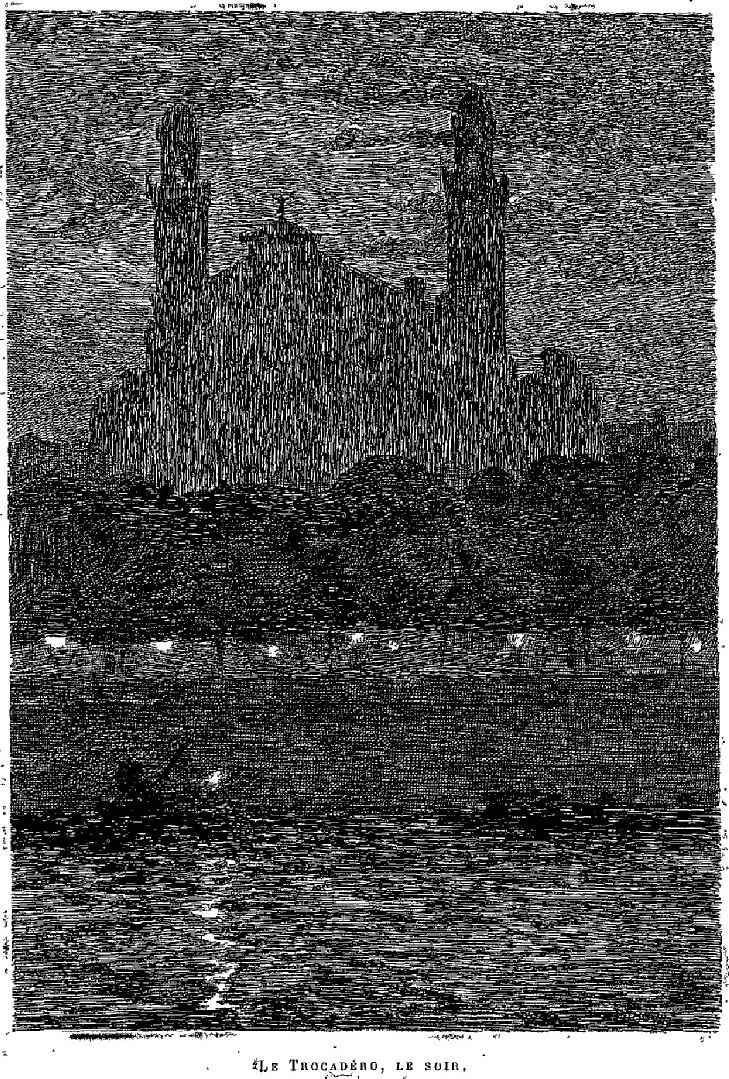

The illustrations that ultimately appeared in “Les quais de Paris” typically show people hard at work tying up boats, moving cargo, and turning winches. One detail from the present sheet that did end up in the essay is the distant twin-towered building. It is the Trocadéro Palace, a bombastic meeting hall constructed for the 1878 Exposition Universelle. Named for an 1823 battle in which French forces helped Spain’s Bourbon king put down a rebellion, the palace was a mix of architectural references. Many Parisians hated it. Bouyer called it “un témoignage récent de notre art dans un décor hâtif” (a recent testimony to our art in an ill-considered style). The palace’s upper levels would be demolished in 1936 to make way for the “moderne” colonnade complex of the Palais Chaillot for the 1937 Exposition Universelle. In Jouve’s illustration, the original Trocadéro hovers above a tree-lined riverbank at night (fig. 2). Its dreamy, ethereal appearance undoubtedly satisfied Bouyer’s desire that artists see Paris anew through the lens of their imagination.

GPW and TER

Notes

Raymond Bouyer, “Les quais de Paris,” Revue de l’Art Ancien et Moderne, vol. 14, no. 78 (September 1903), pp. 249–54ff., and no. 79 (October 1903), pp. 331–36ff. The Revue was published in Paris from 1897 to 1937, except for the years 1915–19. ↩︎

Jouve had already distinguished himself in 1900 by providing designs for the grand prize–winning frieze at the entrance to the Exposition Universelle. Though the gate has been demolished, sections of the frieze are in the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest. The one showing a bull is clearly monogrammed by Jouve and signed by Alexandre Bigot. In 1901 Jouve provided all the illustrations, some satirical, some harrowing, for the November 23, 1901, issue of Samuel Sigismond Schwarz’s new journal L’Assiette au Beurre, on the theme of social vengeance.

At about the time he made Man along the Seine with a View of the Old Trocadéro, Jouve established his relationship with gallerist Siegfried Bing and his close lifelong friendship with Bing’s son, the sculptor and jewelry designer Marcel. See Gabriel P. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style, 1900 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986), p. 280, no. 25; and Gabriel P. Weisberg, Edwin Becker, and Évelyne Possémé, eds., The Origins of L’Art Nouveau: The Bing Empire (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2004), p. 269. ↩︎

The left-leaning stance of L’Assiette au Beurre and the nature of Jouve’s 1901 contributions to it (see note 2) are other indications of Jouve’s sensitivity to the plight of his subject. ↩︎