61. Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, Study for “Breton Women at a Pardon”

| Artist | Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, French, Paris 1852–Quincey, Haute-Saône 1929 |

| Title, Date | Study for “Breton Women at a Pardon”, 1889 |

| Medium | Graphite with white highlights on beige tracing paper |

| Dimensions | 11 3/8 × 9 1/16 in. (28.9 × 23 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower right: PAJ Dagnan-B / 1889 |

| Provenance | [Galerie Franck Accart, Paris, until 2012; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Exhibition History | "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| Credit Line | Promised gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Minneapolis |

Trained as an academic painter under Alexandre Cabanel (cat. no. 44) and Jean-Léon Gérôme, P. A. J. Dagnan-Bouveret slowly broke with the classical tradition to become a naturalist. His numerous paintings of the 1870s and 1880s were viewed as breathing new life into the academic tradition and were readily accepted at the Salons. Broadcast thus, Dagnan-Bouveret’s work helped to establish a new direction for artists trained at the French academy.1

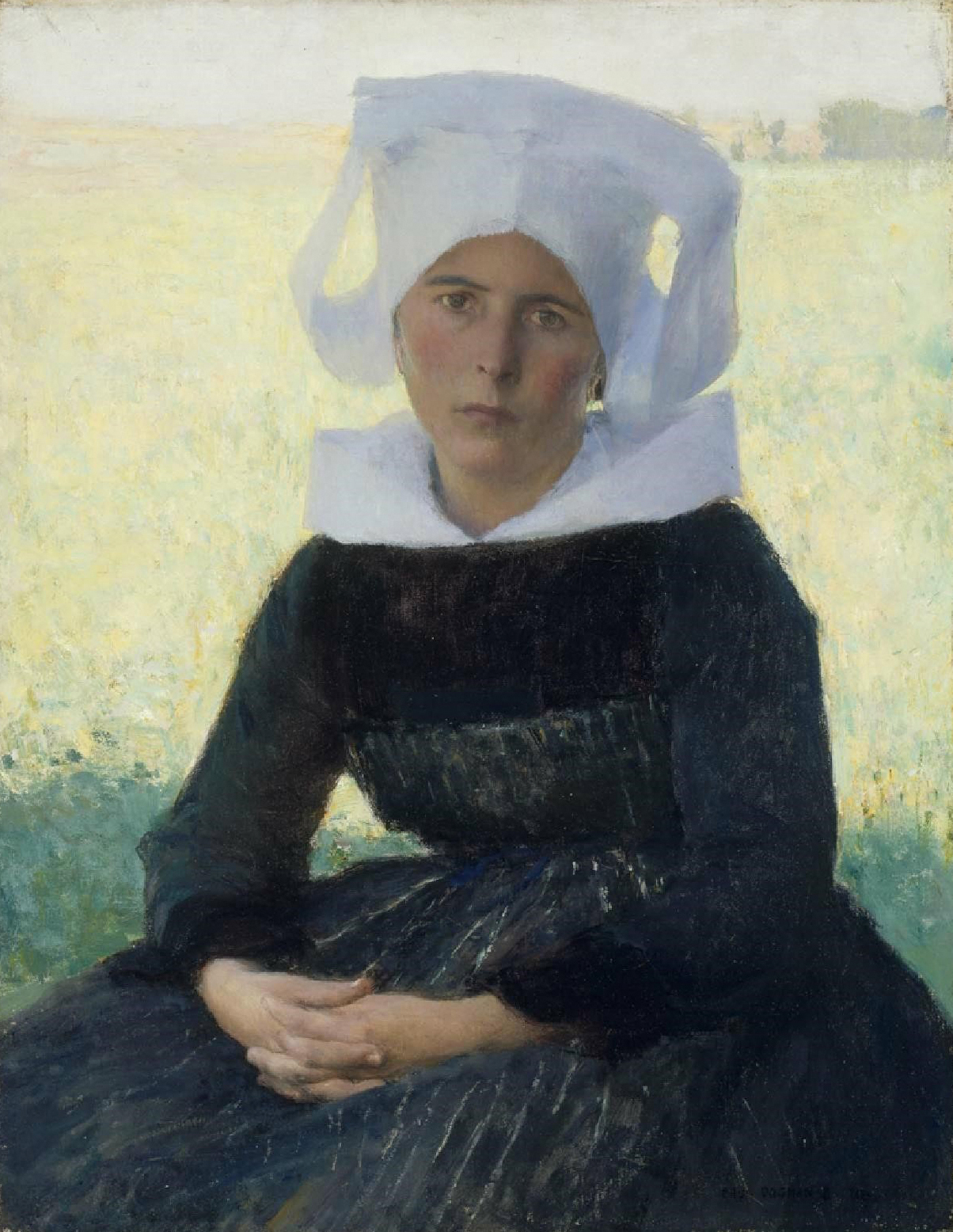

The present study is preparatory to the 1887 oil Breton Women at a Pardon (fig. 1), one of Dagnan-Bouveret’s masterpieces. Depicting attendees of a Pardon was not an isolated phenomenon in nineteenth-century art. The Pardon was a heralded annual folk custom in Brittany dating to the third century CE and the efforts of Celtic monks to convert the pagan population to Christianity. The ceremony attracted countless artists—probably less for its religious meaning than for its pageantry. On the feast day of the patron saint of the local church, community members donned traditional costumes and moved in procession to a site dedicated to the saint. There they prayed and received remission for their sins. Dagnan-Bouveret returned to the Pardon theme several times during his career, starting in the mid-1880s.

Creating the oil Breton Women at a Pardon involved several steps, most notably the use of photography (fig. 2). Dagnan-Bouveret took photographs of potential subjects, then made drawings or pastels of single figures on separate pieces of paper. He assembled these on a wall (fig. 3) to visualize the composition. He went back and forth between photos and sketches until he perfected the arrangement (fig. 4). The final painting was a great success. Critics applauded Dagnan-Bouveret not only for his selection of theme but also for his precise depictions and deft use of photography.

Many viewers were amazed that this important religious event was rendered with such apparent exactitude, not realizing that it was an imaginative construction: Dagnan-Bouveret had set the women, dressed in Breton costumes, in a field near his home in the Franche-Comté area in northeastern France. Naturalist paintings such as this were not simply enlarged color reproductions of photographs, however; they were works of imagination that used photography as a tool.

It is unclear how many studies Dagnan-Bouveret made for Breton Women at a Pardon, but we know there were many. The present drawing relates most closely to the outward-facing figure sitting second from the right in the painting. If his figures vary from their preparatory studies, it’s because the artist modified his images along the way, sometimes using tracing paper to reverse orientation. In 1887 he portrayed the central figure alone, this time with a different bonnet and background (fig. 5).

The present study is dated 1889, two years after the painting. One explanation may be that artists sometimes gave drawings to friends, and dated them with the year they made the gift.

GPW

Notes

Gabriel P. Weisberg, Against the Modern: Dagnan-Bouveret and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition (exh. cat.), Dahesh Museum of Art, New York (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2002), pp. 89–96. Included are examples of the drawings and photographs made in preparation for Breton Women at a Pardon. ↩︎