53. François-Nicolas Chifflart, Rhadamistus Lowering Zenobia into the Araxes River

| Artist | François-Nicolas Chifflart, French, Saint-Omer 1825–Paris 1901 |

| Title, Date | Rhadamistus Lowering Zenobia into the Araxes River, 1856 |

| Medium | Black chalk and charcoal heightened with white chalk on gray-green wove paper |

| Dimensions | 19 7/16 × 19 3/8 in. (49.4 × 49.2 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Stamp of sale (on original lining): VENTE /. / CHIFFLART (Lugt 3925) |

| Provenance | Sale, Vente Chifflart, Paris, Me H. Bricou, expert A. Abram, December 27–28, 1901, no. 74, with the title “Abandonnée.” [Galerie de Bayser, Paris (1985)]; [Shepherd Gallery, New York (1986)]; to Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis (until 2008; given to Mia) |

| Exhibition History | Galerie de Bayser, Paris, 1985; Shepherd Gallery, New York, 1986; "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection," Minneapolis Institute of Arts (2008) and Snite Museum of Art, Notre Dame, Ind. (2010); "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| References | Charles Revillion, "Recherches sur les peintres de la ville de Saint-Omer" (Saint-Omer: Impr. de H. d’Homont, 1904), p. 62; Galerie de Bayser, Paris (exh. cat.), 1985, no. 14, ill., as "Persée et Andromède"; Shepherd Gallery, New York, "French Nineteenth Century Watercolors, Drawings, Pastels, Paintings and Sculpture" (exh. cat.), vol. 1 (Spring 1986), no. 38, ill., as "Perseus and Andromeda"; Valérie Sueur, "François-Nicolas Chifflart (1825-1901)," Mémoire de l’École du Louvre, 1991, vol. 4, D. 16; Lisa Dickinson Michaux with Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection" (exh. cat.), Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis, 2008), p. 28, fig. 10 |

| Credit Line | Gift of Gabriel P. Weisberg and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg in memory of Sarah S. Weisberg 2008.56 |

This work is an outlier in the Weisberg Collection. As an academic drawing featuring an obscure moment of high drama in classical history, it serves as a foil for the many images of everyday experience that form the core of the collection. The draftsman is François Chifflart, then a young painter trying to make his mark in the highly regimented world of French academic painting.1 Teachers in his hometown of Saint-Omer, near the northern tip of France, considered Chifflart a prodigy as a draftsman, painter, and musician. In 1844 he moved to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. He showed early promise as a painter, winning third prize in the 1850 Prix de Rome (Rome Prize) competition and placing first the following year. Each year, Prix de Rome contestants had to paint a picture on a set theme. The assigned theme for 1850 was Zenobia on the Banks of the Araxes River, a subject closely related to that of the present drawing.2

As recounted by the Roman author Tacitus (c. 56–c. 120 CE), the tale of Zenobia and her husband, Rhadamistus, involves incest, intrigue, murder, and sacrifice.3 Zenobia was the daughter of Mithridates, the king of Armenia, and his wife, who was also his niece and the daughter of the king of Iberia. Though their roots were in Iberia rather than Armenia, they had been installed by the Roman Emperor Tiberius and had the support of his successors Caligula and Claudius. Rhadamistus, also a son of the Iberian king, was thus the brother or half-brother of Zenobia’s mother. What could go wrong?

In the year 51 CE, Rhadamistus successfully usurped the throne after smothering his father-in-law, Mithridates, to death. He also killed his sister, the queen, as well as Zenobia’s brothers as they grieved for their parents. With Zenobia as his queen, Rhadamistus ruled Armenia until 55 CE, though his tenuous grasp on power led to his temporary ouster by his Parthian neighbors. Eventually, the Parthians drove Rhadamistus and the pregnant Zenobia out of Armenia and back toward Iberia on horseback.

The ride proved too arduous for Zenobia. Preferring an honorable death to the shame of capture, she begged Rhadamistus to kill her. His efforts to cheer and cajole her failed. Admiring her heroic determination, he stabbed her with his scimitar. Believing that he had killed her, he dragged her body to the banks of the Araxes River4 and laid her in the current. Rhadamistus fled home to Iberia. Zenobia, however, was not dead. Wounded but still breathing, she came to rest downstream, where she was discovered by shepherds who nursed her back to health. Upon learning her story, they delivered her to the Parthian king, who took her into the royal household. To prove his loyalty to the Roman emperor, Rhadamistus’s father had Rhadamistus executed as a traitor.

The present sheet shows us the moment when Rhadamistus has arrived at the Araxes. Powerfully built, he supports the half-clothed Zenobia with his right arm while restraining his horse with his left. Her pale body hangs limp, but we see neither wound nor blood.5 The couple is on a high embankment, the steepness of which Chifflart indicated with vertical lines. There is a small suggestion of the river at the lower right. The action takes place beneath a dramatic sky, whose swirling clouds conveniently highlight Rhadamistus’s arm and the horse’s head.

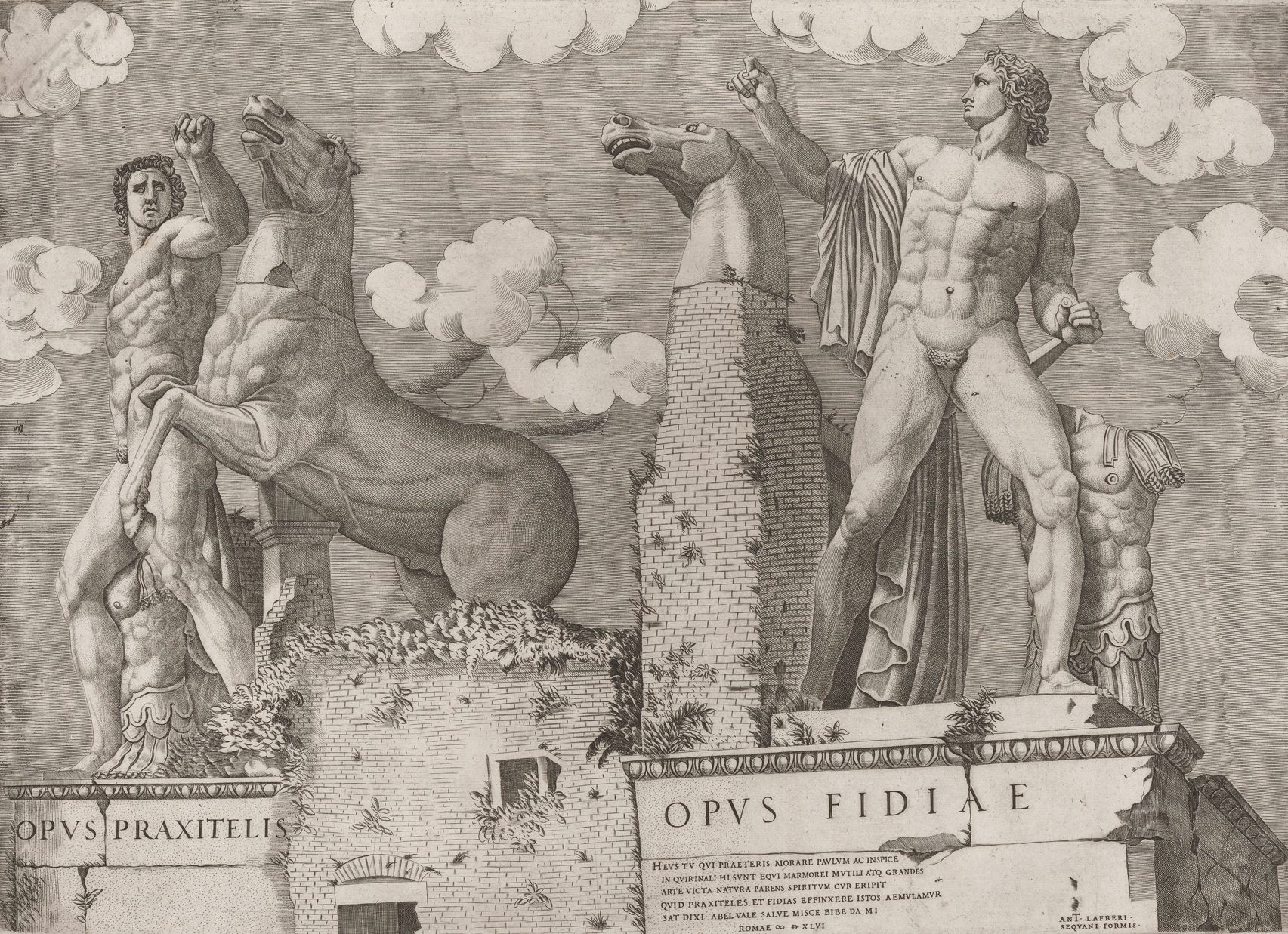

Some critics have complained that Chifflart was too overt in his quotations of works of art that inspired him.6 Here, the grouping of Rhadamistus and his horse calls to mind the famous sculptures of Castor and Pollux—also known as the Horse Tamers—prominently sited on Rome’s Quirinal Hill (fig. 1). During his years in Rome, Chifflart would have been able to study these firsthand.

Chifflart intended this drawing as preparation for a painting that is now lost.7 The canvas was displayed at the Villa Medici in Rome in 1857 and again the same year at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The general composition was recorded in a print completed by 1859 (fig. 2).8 Since the painting is lost, we do not know whether its format was square, like the Weisberg drawing, or upright, like the print.

Despite his early success as a painter, Chifflart had a personality unsuited to the upper echelons of the art world. During his five-year sojourn at the Villa Medici—his reward for winning the Prix de Rome in 1851—he gained notice as an exceptionally individual character. Melancholic and unsociable, he could not play the game that would lead to big commissions.

He eventually developed printmaking and drawing as his main professional outlets. Ultimately, he sank into obscurity and died a forgotten man.

TER

Notes

For a biography of Chifflart, see Valérie Sueur, François Chifflart, graveur et illustrateur (exh. cat.), Musée d’Orsay (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), pp. 5–17. ↩︎

Valérie Sueur, “François-Nicolas Chifflart (1825–1901),” Mémoire de l’École du Louvre, 1991, vol. 4, p. 28. The composition of the painting is known through two related drawings; see D. 4 and p. 28. ↩︎

Tacitus, The Annals, book 12, chaps. 44–51. ↩︎

Also known as the Aras River, it is the western border of Armenia, with Cappadocia—modern-day eastern Turkey—on the other side. ↩︎

One of the two winning entries in the 1850 Prix de Rome competition, that of Paul Baudry, shows the moment in the story when the shepherds have discovered Zenobia’s body. Baudry clearly showed a stab wound below her right breast. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, the other winner, also painted the discovery by the shepherds, but he showed her more fully clothed, with no wound exposed. ↩︎

Michael Howard describes Chifflart’s references as “ill-digested” in his article for Grove Art Online (https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T016444). Chifflart’s guiding star was Michelangelo, but the work of other artists from antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and French Romanticism piqued his interest as well. ↩︎

Sueur 1991, p. 48. ↩︎

Sueur 1991, G. 4. The print is part of the portfolio “Œuvres de M. Chifflart, grand prix de Rome,” published by Alfred Cadart, Chifflart’s brother-in-law. It included original prints by Chifflart, reproductive prints by others, and photographs of paintings. It is not entirely clear to me whether the Zenobia print was made by Chifflart or another printmaker. See Henri Beraldi, Les graveurs du XIXe siècle, guide de l’amateur d’estampes modernes (Paris: Librairie L. Conquet, 1886), vol. V, p. 8, no. 1. See also Valérie Sueur, “L’Album Chifflart (1859): statut et rôle de l’image au milieu de XIXe siècle,” Nouvelles de L’Estampe (October 1993), no. 130-131. ↩︎