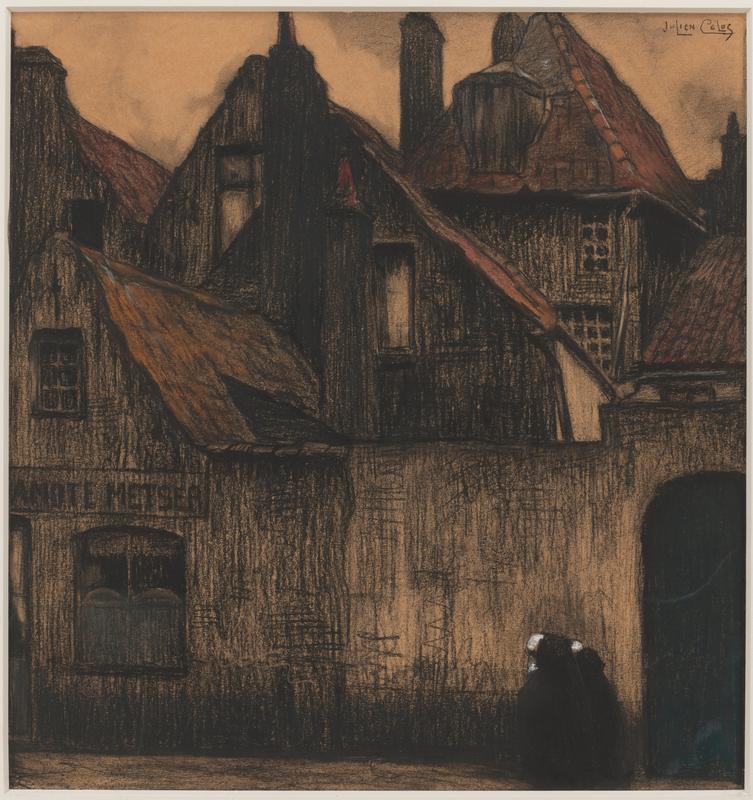

47. Julien Celos, The Dead City, Bruges

| Artist | Julien Celos, Belgian, Antwerp 1884–Antwerp 1953 |

| Title, Date | The Dead City, Bruges (Die tote Stadt, Brügge), c. 1911 |

| Medium | Charcoal, pastel, and chalk |

| Dimensions | 18 1/2 × 17 1/2 in. (47 × 44.5 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Upper right: Julien Celos |

| Provenance | Sale, Antiquités, tableaux, objets d’art et bijoux, Galerie Moderne, Brussels, April 26–27, 2005, no. 796. [Galerie Maurice Tzwern, Brussels, until 2007; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis (2007–21; given to Mia) |

| Exhibition History | "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| Credit Line | Gift of Dr. Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg 2021.131.3 |

These two black-clothed figures are Beguines religious laywomen who lived quasi-monastic lives in beguinages.1 The order thrived from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries, with the beguinage often becoming a sanctuary for widows. Just a few of these communities remained in Julien Celos’s time.2 They were no less vital as religious paths for single women but by then were seen as romantic remnants of the past.

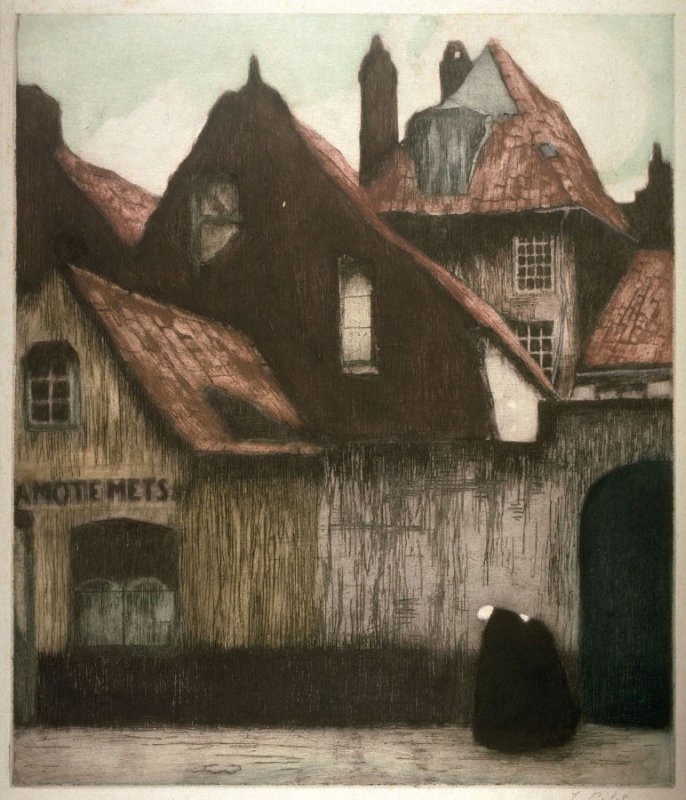

The present drawing is apparently the basis for Celos’s color etching The Dead City, Bruges (Die tote Stadt, Brügge) (fig. 1). Although the artist was born and educated in Antwerp, Belgium, just east of Bruges, the print was published in Vienna, which explains the German title.3 In both drawing and print, the hunched figures are cloaked in mystery, dwarfed by melancholy architecture.

This image is very likely inspired by Georges Rodenbach’s famous symbolist novel Bruges-la-Morte (1892). The author repeatedly mentions Beguines, writing that when they circulate through Bruges, they seem not to walk but rather to glide like swans. One of the characters, Barbe, envies the peace of these women’s lives and hopes to enter their community as a final refuge before death. (Ultimately, the cloister’s moral rigidity ruins her dreams.) In the present drawing, Celos picked up on the image of Beguines gliding through the desolate city, a city with a dark character of its own. Bruges has long been freighted with meaning. It possesses a glorious past steeped in trade, banking, textile production, and ducal grandeur, while also being a wellspring of mysticism with its churches, monasteries, convents; Christ’s blood was reputedly brought from the Holy Land to the city by a twelfth-century count.4

Rodenbach illustrated the first edition of his book with about twenty black-and-white photographs of Bruges,5 marking the first time a work of fiction was illustrated with photos. The author explicitly stated that he saw Bruges as a character that helps shape the narrative; the city is linked to every event in the book.6 One of the few times Rodenbach’s photos show a human presence is a scene of Beguines and nuns returning to the beguinage (fig. 2).7

Celos is best known for depicting old towns in Holland and Belgium, mostly in oil paint and color etchings. The specific location here, however, is unknown. There may be a clue in the shop sign at left, which reads “AMOTE METSER.” Metser means mason or bricklayer in Dutch and Flemish. Whether “AMOTE” is cut off or a complete word is unclear.

GPW

Notes

When the drawing was auctioned at Galerie Moderne, Brussels, in 2005, it was listed as Béguine dans les ruelles (Beguine in the Alleys). ↩︎

Celos’s name is sometimes spelled with an accent: Célos. ↩︎

Published by Verlag der Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst, Vienna. An impression is at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (inv. 11.46033.4), https://collections.mfa.org/objects/75439/die-tote-stadt-brugge-the-dead-city-bruges?ctx=48d1a169-76f7-42a5-93ef-e205613a7c30&idx=0. The Achenbach Foundation, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, catalogues its impression under the title Old Continental House (inv. 1963.30.12048), https://www.famsf.org/artworks/old-continental-house ↩︎

See Lynne Pudles, “Fernand Khnopff, Georges Rodenbach, and Bruges, the Dead City,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 74, no. 4 (December 1992), pp. 637-54. ↩︎

Georges Rodenbach, Bruges-la-Morte (Paris: Librairie Marpon and Flammarion, 1892). The photographers were Lévy Fils et Cie and Neurdein Frères. The photogravures were made by Ch.-G. Petit. ↩︎

Rodenbach, 1892, p. ii. ↩︎

Rodenbach, 1892, p. 108, pl. 10. ↩︎