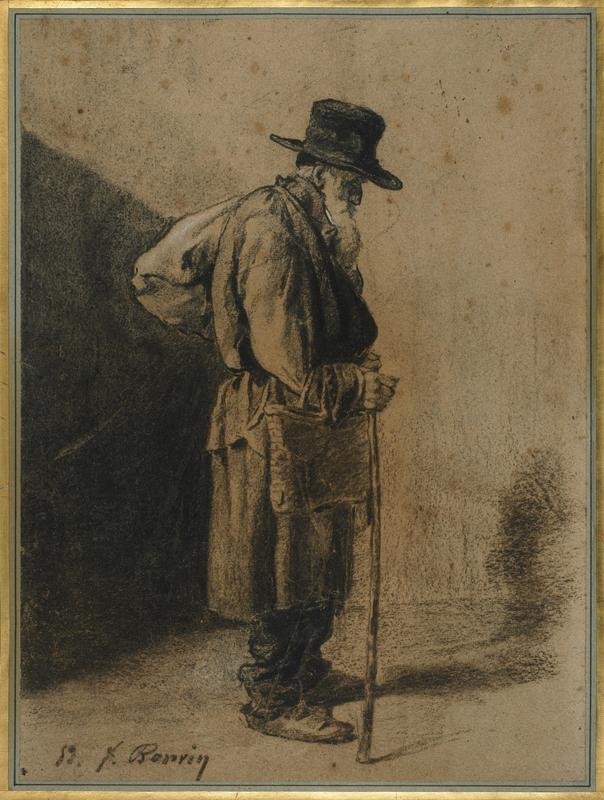

28. François Bonvin, The Old Beggar (also called The Ragpicker or Chiffonier)

| Artist | François Bonvin, French, Paris 1817–Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1887 |

| Title, Date | The Old Beggar (also called The Ragpicker or Chiffonnier), 1853 |

| Medium | Black, brown, and white chalk on tan wove paper |

| Dimensions | 15 × 11 3/16 in. (38.1 × 28.4 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower left: 53. f. Bonvin |

| Provenance | Charles Jacque Collection; [Hazlitt Gallery, London, until 1974; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Exhibition History | "The Realist Tradition: French Painting and Drawing 1830–1900," Cleveland Museum of Art and other venues, 1980–81; "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection," Mia (2008) and Snite Museum of Art, Notre Dame, Ind. (2010); "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| References | Gabriel P. Weisberg, "François Bonvin and the Critics of His Art," "Apollo" (October 1974), p. 307, fig. 3; Weisberg, "The Traditional Realism of François Bonvin," Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 65, no. 9 (November 1978), p. 286, fig. 11; Weisberg, "Bonvin," trans. André Watteau (Paris: Éditions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1979), no. 244; Weisberg, "The Realist Tradition: French Painting and Drawing 1830–1900" (exh. cat.), Cleveland Museum of Art and other venues (Cleveland, 1980), pp. 45–47, no. 6; Weisberg, "Le retour des réalistes," "Connaissance des Arts," no. 345 (November 1980), p. 66; Lisa Dickinson Michaux with Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection" (exh. cat.), Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis, 2008), pp. 14–15, fig. 2 |

| Credit Line | Promised gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Minneapolis |

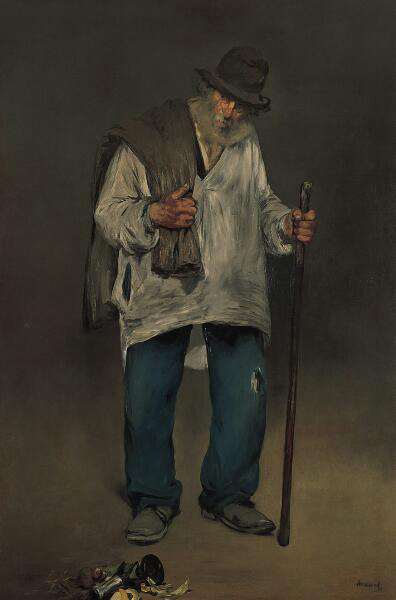

François Bonvin’s choice of subject was motivated by the large number of beggars and ragpickers he encountered almost daily during France’s Second Empire, led by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte. Other artists took up the theme in prints, drawings, and paintings (fig. 1).1 Unlike beggars, ragpickers had a job. They were licensed by the government and had a right to pursue their occupation, however lowly it may have been. It appears that Bonvin was captivated by the profession, as he devoted an entire series of drawings to it. He undoubtedly found this person on the street and invited him into his studio to pose.

Bonvin used chalk to suggest a rough effect, a manner appropriate to his subject. A ragpicker’s basic accoutrements were a long stick (sometimes with a hook at one end) for picking up discarded objects, and a sack or basket for collecting the day’s haul, which would then be sold. Ragpickers symbolized the place of downtrodden people in society and their right to exist. They were seen as prophets of the poor, as people who could speak truthfully about their condition. Indeed, Bonvin’s intense observation of his subject, who appears pensive and self-contained, lends him an air of dignity.

On a personal note, Yvonne and I acquired this in the 1970s. It was our first realist drawing and foreshadowed the direction our collecting would take in the ensuing decades.

GPW

Notes

On the subject of the ragpicker in general and Édouard Manet’s work in particular, see Shira Gottlieb, “Aging and Urban Refuse in Édouard Manet’s The Ragpicker,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 18, no. 2 (Autumn 2019). ↩︎