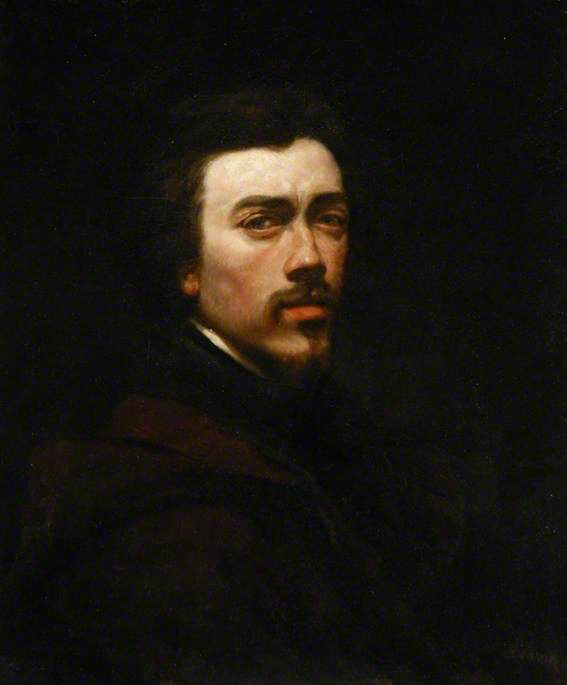

26. François Bonvin, Self-Portrait

| Artist | François Bonvin, French, Paris 1817–Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1887 |

| Title, Date | Self-Portrait, 1847 |

| Medium | Pen and brown and black ink over wash on cream wove paper |

| Dimensions | 5 5/8 × 4 3/4 in. (14.3 × 12.1 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower left: f. Bonvin 47 |

| Provenance | French auction, with help from Jacques Foucart, 1976; to Weisberg; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Exhibition History | "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection," Mia (2008) and Snite Museum of Art, Notre Dame, Ind. (2010); "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| References | Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Bonvin," trans. André Watteau (Paris: Éditions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1979), p. 253, no. 222, ill.; Lisa Dickinson Michaux with Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection" (exh. cat.), Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis, 2008), p. 16, fig. 3 |

| Credit Line | Promised gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Minneapolis |

Around the time François Bonvin was painting his dramatic self-portrait of 1847 (fig. 1), he paused to draw this small, captivating study. With quick, deft strokes of his pen, he produced an intimate likeness, which he then shrouded in mystery by brushing on dense washes. Very likely he had in mind the work of seventeenth-century Dutch artists—specifically the many self-portraits by Rembrandt (figs. 2–3).

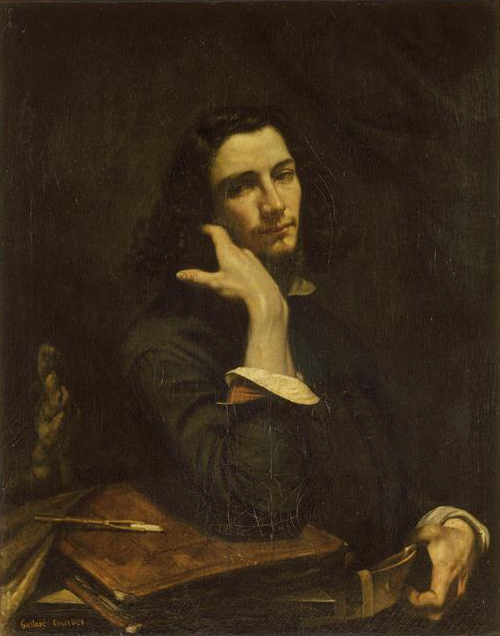

It is unclear when Bonvin first became acquainted with Dutch art. One avenue may have been his ties with private collectors such as Laurent Laperlier, whose collection contained many Dutch works. Another possible conduit was his friend Gustave Courbet (1819–1877). In 1846 Courbet painted a portrait of Bonvin, now lost. For a sense of what it looked like, we can look to Courbet’s self-portraits of the time. His Man with a Leather Belt (fig. 4), for example, combines the affectedness of Anthony van Dyck with the forceful chiaroscuro of Rembrandt. Courbet was so interested in the work of Dutch and Flemish old masters that he traveled to the Low Countries in 1846 and 1847 to see their work. It would have been hard for Bonvin not to share in his friend’s enthusiasm. The Louvre provided Bonvin with more Dutch examples; in about 1850 he reportedly applied to be a copyist there.

While other self-portraits by Bonvin exist, none possesses the spontaneity displayed here. He also used this small study to reveal something of his workaday life. On his head is the cap of the Paris Prefecture of Police, where he worked as a clerk until he could sustain himself through his art.

GPW and TER