6–7. Adolphe Appian, Landscape at Sunset and Woman Seated at the Edge of a Pond

| Artist | Adolphe Appian, French, Lyon 1818–Lyon 1898 |

| Title, Date | Landscape at Sunset, 1863 |

| Medium | Charcoal and wash with stumping and scratching on yellow paper |

| Dimensions | 23 1/8 × 34 1/2 in. (58.7 × 87.6 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower right: Appian 1863 |

| Provenance | Private collection, Lyon; [Galerie Paul Prouté S. A., Paris, until 2001; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Exhibition History | "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2008; "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| References | Lisa Dickinson Michaux with Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Expanding the Boundaries: Selected Drawings from the Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg Collection" (exh. cat.), Minneapolis Institute of Arts (Minneapolis, 2008), pp. 68, 70, fig. 39 |

| Credit Line | Promised gift of Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg, Minneapolis |

| Artist | Adolphe Appian, French, Lyon 1818–Lyon 1898 |

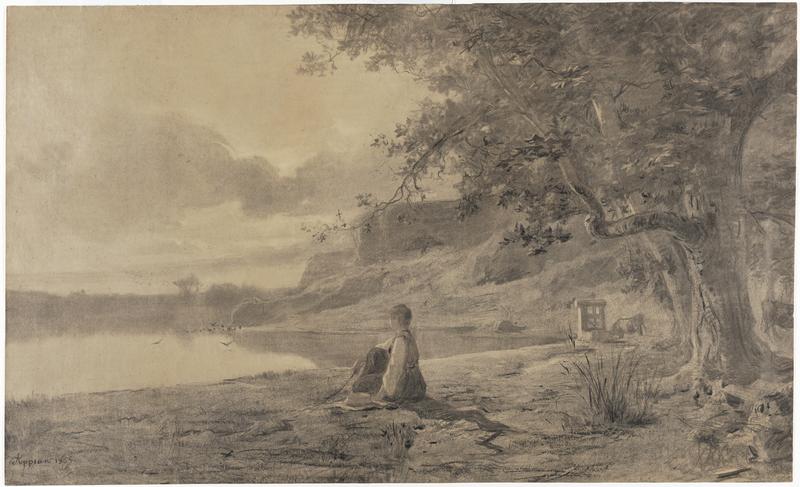

| Title, Date | Woman Seated at the Edge of a Pond, 1865 |

| Medium | Charcoal and wash with stumping and scratching |

| Dimensions | 18 3/4 × 30 3/4 in. (47.6 × 78.1 cm) |

| Inscriptions + Marks | Lower left: Appian 1865 |

| Provenance | Private collection, Lyon; [Galerie Paul Prouté, Paris]; [Armstrong Fine Art, Chicago, until 2021; to Weisberg]; Yvonne and Gabriel Weisberg, Minneapolis (2021–22; given to Mia) |

| Exhibition History | "Reflections on Reality: Drawings and Paintings from the Weisberg Collection," Mia, 2022–23 |

| Credit Line | Gift of Dr. Gabriel P. and Yvonne M.L. Weisberg 2022.80.2 |

Adolphe Appian specialized in landscapes, two of which are represented in the Weisberg Collection. Hailing from Lyon, a city renowned for its silk industry, Appian trained early on in the design of luxury fabrics.1 He served an apprenticeship, then established a partnership to produce textile designs. The venture soon failed. Cultivating a bohemian persona, he made ends meet by teaching drawing, restoring paintings, painting wall decorations, and performing: he was a versatile musician, playing the cornet, piano, and flute. He married in 1848, but the following year his wife died from complications of childbirth; the infant perished, too. In 1852 Appian decided to devote his time to painting and drawing—and, eventually, printmaking.2 While painting in Crémieu, a medieval town just east of Lyon, he befriended the Barbizon landscape painters Camille Corot and Charles Daubigny. He credited them with helping him to see nature better; he realized that simplicity and intimacy could yield great beauty. In 1853 the tireless artist had two works accepted by the Paris Salon. The next year, because there was no Paris Salon, Appian went to the village of Marlotte in the forest of Fontainebleau. The area was a mecca for artists, and he would return each summer for several years. He also began to explore southeastern France, recording sites in such areas as Savoie, Ain, Isère, and Rhône. He traveled from the Pyrenees to the plains, in forests, villages, and fields. His exhibition entries became more numerous, and their placement more prominent. Good reviews helped his work sell, but he and his second wife still found themselves sometimes short of money.

Appian’s breakthrough occurred in 1866, not long after he executed the present drawings. Emperor Napoleon III and Princess Mathilde bought two of his paintings, each for the grand sum of 2,000 francs. The next year he made another big sale to a government minister. In 1868 he finally won a gold medal at the Paris Salon. Appian would speak often of the moment he received the medal and took the emperor’s hand. After this, his itineraries included more glamorous destinations: Lake Geneva, Évian, Monaco, and Venice. By the end of the 1870s, he was able to buy a medieval building in Lyon with a splendid view of Mont Blanc and build a lavish studio on its grounds. He called his home Villa des Fusains—something of a pun, since fusain is the name of a flowering shrub in his garden and also the French word for a charcoal drawing. The remainder of his career was uneven. It appears that toward the end, his work appealed less to the Parisian avant-garde than to those who more closely identified with his pastoral aesthetic. Nonetheless, his achievements were widely lauded. He was made a knight of the Legion of Honor in 1892 and received a special gold medal two years later at the Salon in Lyon, where he was revered.

As we can see in the Weisberg landscapes, Appian frequently included a contemplative figure near the edge of a body of water beneath open sky. We have not been able to identify the precise location of either view. One suspects that the woman in the 1865 sheet could be his wife, for she often accompanied him on his outings.

In 1880, several years after he made these two drawings, Appian wrote about his technique. He revealed that he liked to draw on wrapping paper, which often had a slightly yellow tint that added warmth to his scenes. (He felt that gray or white paper produced cold, sad effects.) He wet his paper and stretched it over a board, being sure to put cardboard or extra paper beneath this sheet so that the drawing would not be disrupted by the board’s texture. He drew using very soft charcoal. He followed its application with extensive stumping (smudging) and erasure to produce tonal, monochromatic images. He made stumps from strips of rolled cotton—as opposed to the more common paper and leather—because he liked the soft effects he could achieve. He recommended applying charcoal gently in the sky with the side of the stick and then smudging to produce an overall tone. This process was often aided by a clean piece of leather, a white leather glove, or a slightly dampened brush. In addition, Appian found that he could alter the consistency of the charcoal by passing it through his hair so that it picked up a little grease.3 Though not mentioned in his 1880 statement, he also used the subtractive technique of scratching, evident in both Weisberg drawings.

While they share compositional and technical traits, the Weisberg drawings are quite different in effect. Bathed in the warmth of its yellow paper, the 1863 scene of a boy pausing to give his horse a drink at sunset is meticulously finished and offers dramatic tonal contrasts. Intense scratching plays a significant role in making the water sparkle, especially near the dog. The drawing of the seated woman, created two years later, has a much narrower tonal range. The touches of wash are not integrated as subtly into the tonal scheme. Made on white paper, it conveys a cool melancholy. The first drawing is brilliantly luminous; the second, vaporous and interspersed with nervous flicks of the brush. Were it not signed and dated, one might question whether the second work was even finished. Perhaps the unresolved brushstrokes signal Appian’s desire for new effects.

TER

Notes

This sketch of the artist’s life relies heavily on Jacques Gruyer, “Un vie d’artiste,” in Jacques Gruyer, Adolphe Appian (exh. cat.), Musée de Brou (Bourg-en-Bresse, France, 1997), pp. 8–44. ↩︎

Marie-Félicie Perez, “Un aquafortiste d’une rare valeur,” in Jacques Gruyer, Adolphe Appian; Atherton Curtis and Paul Prouté, Adolphe Appian: Son oeuvre gravé et lithographié (Paris: Paul Prouté, 1968). ↩︎

Adolphe Appian, “Pour dessiner les paysages au fusain,” mss. Lyon, May 21, 1880, transcribed in Jacques Gruyer, Adolphe Appian. ↩︎